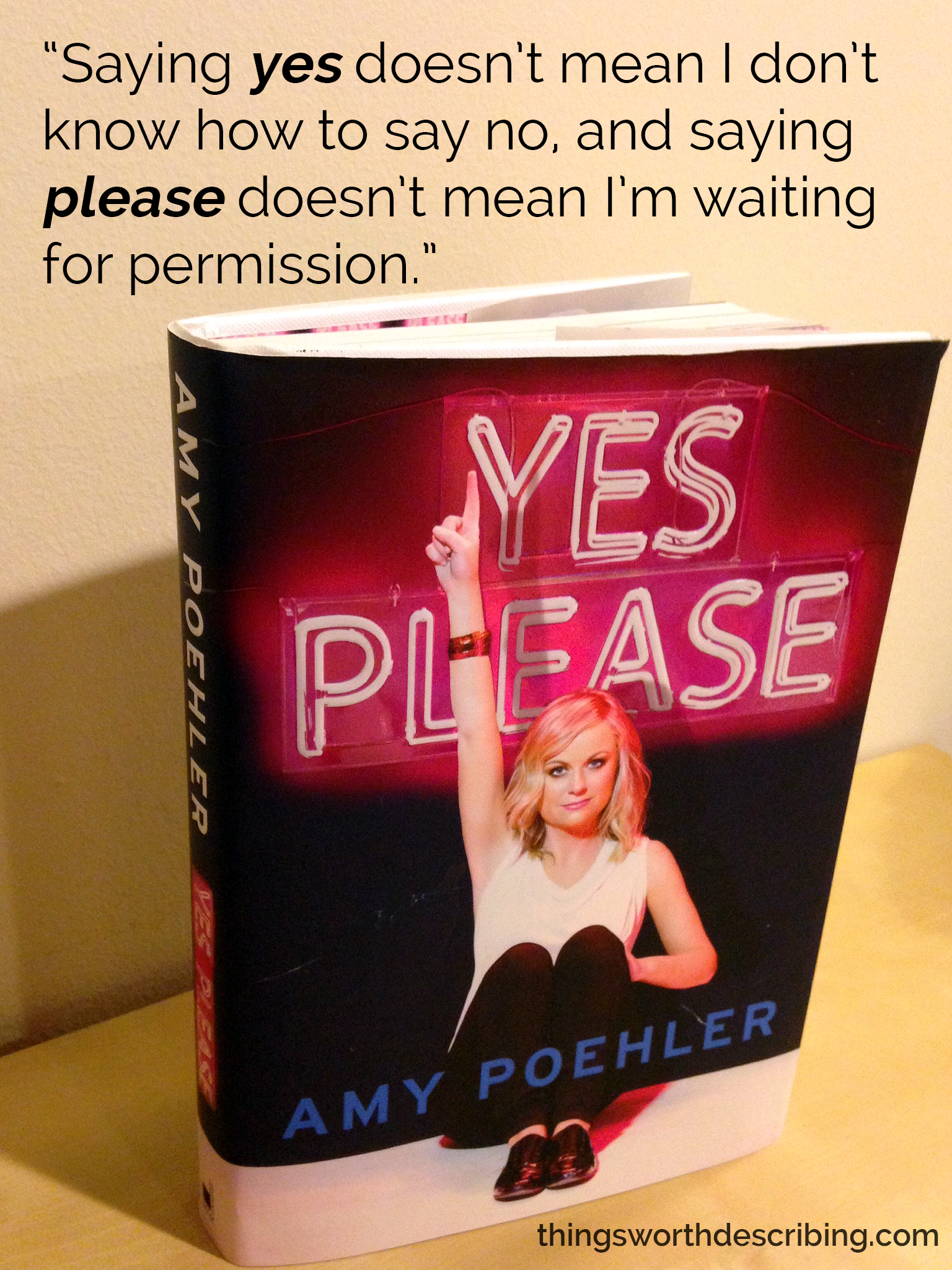

Nov 8, 2014 | books, happenings, news

Amy Poehler has it together. And ‘it’ has nothing to do with fame, money or romance even if she does have all three. You have ‘it’ when you’re happy, which means knowing and loving yourself to the fullest — two things Amy does best.

When I started her new book Yes Please, I still referred to her by her full name. But by the time I finished it, she was just Amy. It’s bizarre how close you can feel to someone you’ve never met, just by reading the stories they chose to share with the entire world. But Amy’s writing voice is so clear and simple that I can almost hear Leslie Knope’s actual voice reading her words aloud.

Amy just seems so real. In the intro she talks about how hard it is to write a book — especially one about yourself — and how implicitly conceited and painfully permanent the whole memoir-publishing process is. So down-to-earth yet somehow sharp and hilarious. Some of the memories she retells are insane celebrity-only kind of stories, but my favorites are the everyday ones. The stories that remind me of my own misadventures.

When she played Dorothy in her fourth grade’s Wizard of Oz, she discovered “on stage” meant “in charge” and improv’d for the very first time. I played Charlotte in Charlotte’s Web in the fourth grade too, but my story ended in the audience’s disappointment instead of delight. I got distracted reading backstage, missed a cue, and realized crowds are the worst and words are my home.

Sure she writes about creating Parks and Recreation and what it was like giving birth to her first son while watching the SNL episode she had rehearsed to perform in days earlier (“Laughing to Crying to Laughing”). But she writes about those things from a perspective anyone can understand. No big words, no convoluted themes, just a girl telling her stories in different ways.

The book’s three parts seem to be in loose chronological order: “Say Whatever You Want,” “Do Whatever You Like,” and “Be Whoever You Are.” “Say” begins with The Wizard of Oz and her birth story while “Be” wraps it up with Parks and Recreation, advice on Hollywood, and the unfathomable love she has for her sons.

The chronology of the three parts align on a larger scope too, with their titles — kids say whatever they want because they just found out they can, teenagers do whatever they want just to prove they can, and adults have the freedom to be whoever they are (the only problem is a lot of people get distracted by shoulds and don’t know who that is).

My favorite essay was “Plain Girl vs. the Demon.” She perfectly captures and personifies the self-doubt that wreaks havoc within all of us:

“And then one day, you go through a breakup or you can’t lose your baby weight or you look at your reflection in a soup spoon and that slimy bugger is back. It moves its sour mouth up to your ear and reminds you that you are fat and ugly and don’t deserve love.

This demon is some Stephen King from-the-sewer devil-level shit.”

Coming to the realization that the negative parts of me don’t have any real control is one of the best epiphanies I can ever remember having. And Amy Poehler knows what that feels like.

Thank YOU Amy, for writing a book for everyone.

Mar 20, 2013 | books

Little Bee tells the story of two women whose lives are accidentally intertwined. The first is a small 16-year-old African refugee who finally escapes two years in the UK’s Immigration Detention Center at the beginning of the book. The second is a British wife and young mother who began a successful women’s magazine before her new family undergoes an overwhelming tragedy (no spoilers here!).

“We must see all scars as beauty. Okay? This will be our secret”

The chapters bounce back and forth between each protagonist, Little Bee and Sarah, with each taking turns narrating their own side of the story. At first its confusing – why are we following these two separate characters? – but Cleave is sure to show the link between the two even from the first chapter. One of Little Bee’s few possessions is a business card belonging to Sarah’s husband, and she uses the printed number to call him as soon as she’s given the chance to use a phone. It takes half the book to discover exactly what terrible tragedy these women experienced together two years prior, but its the deep scarring kind that forges an unbreakable bond between them.

Little Bee came from a small village in Nigeria, escaping when it was overrun by violent men thirsty for oil and money. Her experiences give her a strange combination of innocence and maturity – she understands death more than most but remains fearful of her own sexuality because she’s only witnessed that taken advantage of. She seems younger than 16 because she only just learned English, taking the Queen’s language as her only defense in the dank cells that hold the fugitive immigrants just looking for a better life.

But Little Bee somehow still sees the glass half full – a miracle just on its own. She paints her toes bright red every night in captivity, hiding them under her steel-toed boots so that she can still feel pretty under all that protection. She’s released from the Detention Center with a few other girls, and each are given a clear plastic bag to hold all their worldly belongings. When Little Bee sees a beautiful girl in a yellow sari with nothing in her bag,

“At first I thought it was empty but then I thought, Why do you carry that bag, girl, if there is nothing in it? I could see her sari through it, so I decided she was holding a bag full of lemon yellow. That is everything she owned when they let us girls out.”

She has such a simple outlook on life, whereas Sarah’s couldn’t get any more complicated, and when the two women finally do meet in the book, Sarah does everything she can to help the little girl. She recognizes how smart she is, how kind and how loyal – not to mention how much she could learn from this 16-year-old who has seen more terrible things than she could even imagine.

“Truly there is no flag for us floating people. We are millions, but we are not a nation. We cannot stay together. Maybe we get together in ones and twos, for a day or a month or even a year, but then the wind changes and carries the hope away. Death came and I left in fear. Now all I have is my shame and the memory of bright colors and the echo of Yevette’s laugh. Sometimes I feel as lonely as the Queen of England.”

You can read a Q&A with Chris Cleave about the origins of the book on his website, and the whole incredible book is only $10 on Amazon. Read it to find out what happens for yourself.

Feb 27, 2013 | books

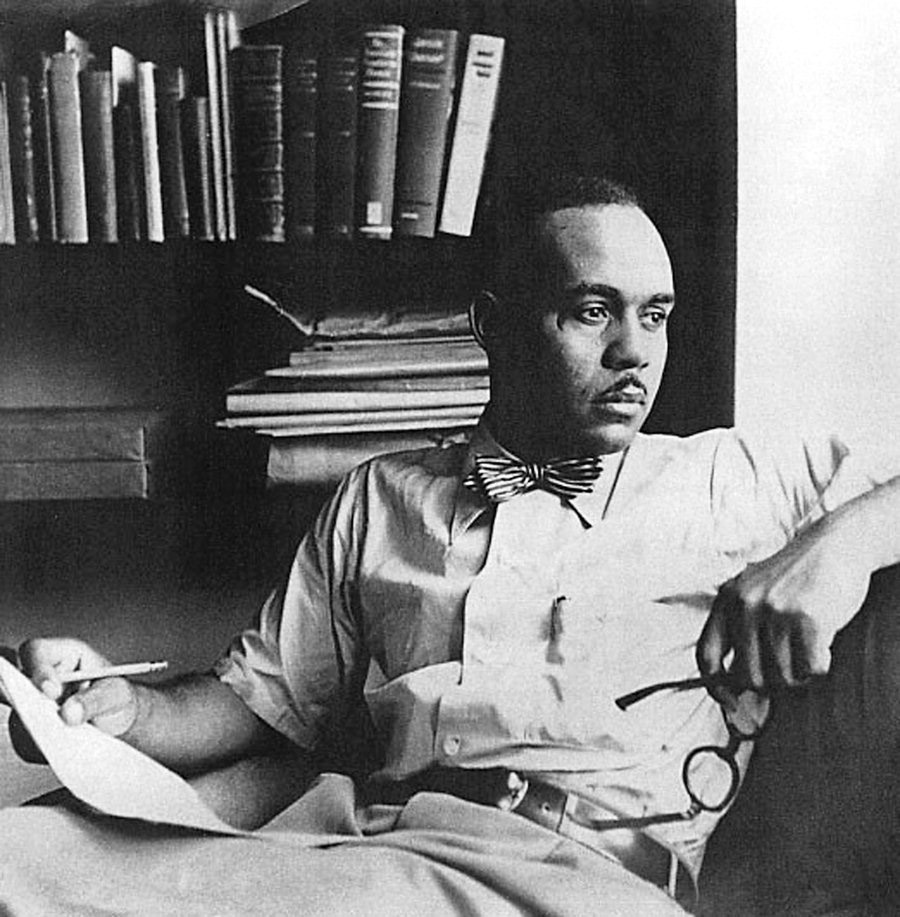

Invisible Man is a dense piece of text, but if you have enough free time and a love for words and African American history then it’s more than worth it.

Invisible Man is a dense piece of text, but if you have enough free time and a love for words and African American history then it’s more than worth it.

Sometimes the words won out over clarity though – the head trauma/hospital scene hardly makes any sense at all. There’s an out of place prologue from our nameless protagonist, where he tells us his current situation: living rent free under the radar in New York City, stealing electricity with a basement apartment covered in lightbulbs – his own personal form of sticking it to the man after years of being taken advantage of.

You’d think that foreshadowing this heavy would ruin the suspense of the entire book, but there’s no way anyone could guess the all the terrible things that happen to this poor boy trying to figure things out for himself – in the south society won’t let him and in the north there’s not a soul who cares.

Finally though he is stabbed in the back too many times to try anymore, going through an aimless wandering phase until he witnesses the eviction of an elderly couple in Brooklyn. The community gathers to watch the police move everything the couple has out onto the street and the scene nearly escalates to a riot when our protagonist feels compelled to speak, and his talent for moving people with words becomes a local news story. The Brotherhood recruited him that night, and even though he just felt lucky to have a job, joining the Brotherhood would be the last self-sacrifice he’d make before realizing how important the self actually is.

His first speech as a Brother (and yes, they all call each other Brother so-and-so) was regarded as a failure by the elder brothers because it relied too much on emotion and too little on the literature detailing the Brotherhood principles that he’d only had a few days to study. The speech was the book’s major highlight, although the story does get a lot more interesting once our protagonist becomes the star of a racial equality , almost cult-like protest movement.

After an anticlimactic beginning interrupted by some mouthy audience members, this “emotional speech” continued,

“There was a stir behind me. I waited until it was quiet and hurried on.

‘Silence is consent,’ I said, ‘so I’ll have it out, I’ll confess it!’ My shoulders were squared, my chin thrust forward and my eyes focused straight into the light. ‘Something strange and miraculous and transforming is taking place in me right now… as I stand here before you!’

I could feel the words forming themselves, slowly falling into place. The light seemed to boil opalescently, like liquid soap shaken gently in a bottle.

‘Let me describe it. It is something odd. It’s something that I’m sure I’d never experience anywhere else in the world. I feel your eyes upon me. I hear the pulse of your breathing. And now, at this moment, with your black and white eyes upon me, I feel… I feel…”

I stumbled in a stillness so complete that I could hear the gears of the huge clock mounted somewhere on the balcony gnawing upon time.

‘What is it, son, what do you feel?’ a shrill voice cried.

My voice fell to a husky whisper, ‘I feel, I feel suddenly that I have become more human. Do you understand? More human. Not that I have become a man, for I was born a man. But that I am more human. I feel strong, I feel able to get things done! I feel that I can see sharp and clear and far down the dim corridor of history and in it I can hear the footsteps of militant fraternity! No, wait, let me confess… I feel the urge to affirm my feelings… I feel that here, after a long and desperate and uncommonly blind journey, I have come home… Home! With your eyes upon me I feel that I’ve found my true family! My true people! My true country! I am a new citizen of the country of your vision, a native of your fraternal land. I feel that here tonight, in this old arena, the new is being born and the vital old revived. In each of you, in me, in us all.

‘SISTERS! BROTHERS!

WE ARE THE TRUE PATRIOTS! THE CITIZENS OF TOMORROW’S WORLD!

‘WE’LL BE DISPOSSESSED NO MORE!’

The applause struck like a clap of thunder.”

The story circles back to the beginning, but without the protagonist obviously ending in his hole in a basement filled with 1,369 lights. The prologue is actually the most interesting part, but only once you’ve read the book already – it references characters not introduced till the 300th page, although the general meaning can still be understood.

It begins,

“I am an invisibile man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids – and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination – indeed, everything and anything except me.”

After a beginning like that, I was hooked, especially with the somber poetic link between race and invisibility. The rest of the book moves more slowly, carefully and eloquently telling the story of a black boy caught between his grandparent’s generation of slavery and his own time – one painfully pushing towards equality, attempting to undo centuries of hateful thinking and misconceptions, even within his own mind.

Feb 19, 2013 | books

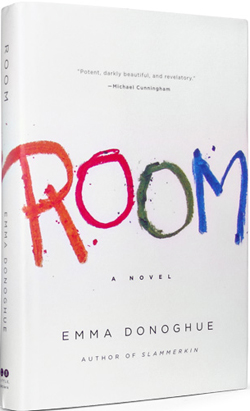

Poor brave little Jack. Room is his story, and he tells it as best he can, often revealing how smart a five-year-old can be – even one who has been locked inside an eleven-by-eleven foot space since birth. He shares his world little by little, allowing you to slowly piece together this adorable little boy’s situation: captivity, held with his mother who was kidnapped long before he was born, Jack himself the product of rape and years of incarceration in a tiny inescapable cell created by a demonic captor known only as “Old Nick.”

At first it feels as if much of the story will be lost on a five-year-old’s perspective, but it becomes very clear very fast that Jack is special, incredibly grateful and mature, and his story ends up being the most important, especially since you’re able to discover the world with him as he learns that all of existence is more than just Ma and Jack and Room.

“Ma’s put a smile on.

She’s tidying Pen back on Shelf.

I ask her, ‘How old are you going to be on your birthday?’

‘Twenty-seven.’

‘Wow.’

I don’t think that cheered her up.”

I don’t want to get into any more of the plot for fear of revealing too much, but this book is absolutely fantastic. Reading Jack’s developing English and explanations for everything allows for a complete immersion in his character. The book made my heart pound with worry and I teared up at least twice, so prepare to have your heart rocked.

Room’s website has an interactive element that was cool at first and then creepy, but it’s worthwhile to check out.

Book excerpt from page 16.

Feb 13, 2013 | books, interviews

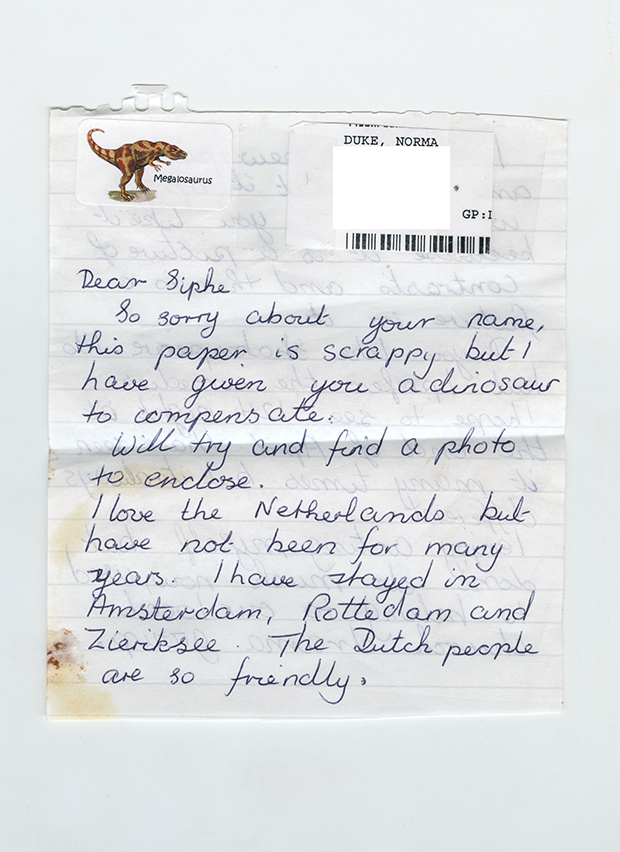

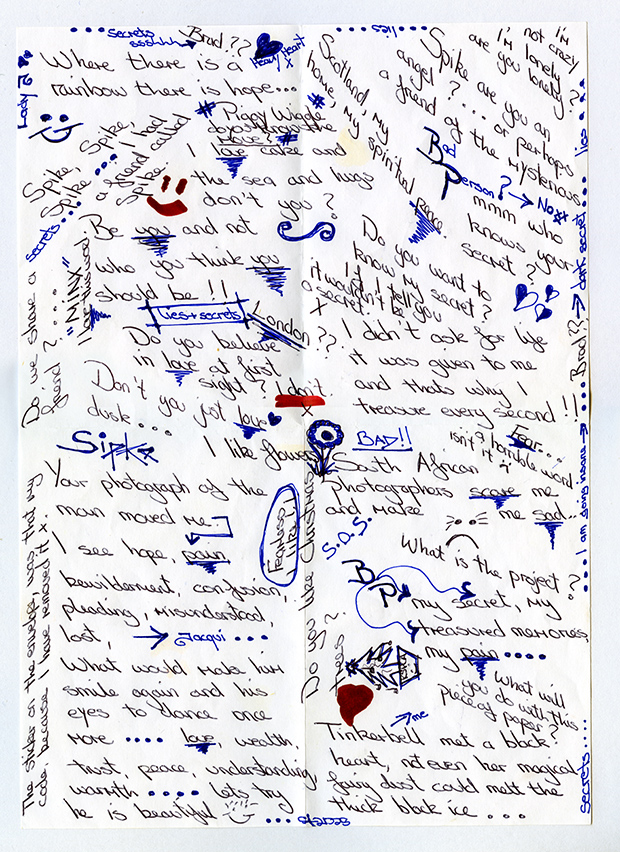

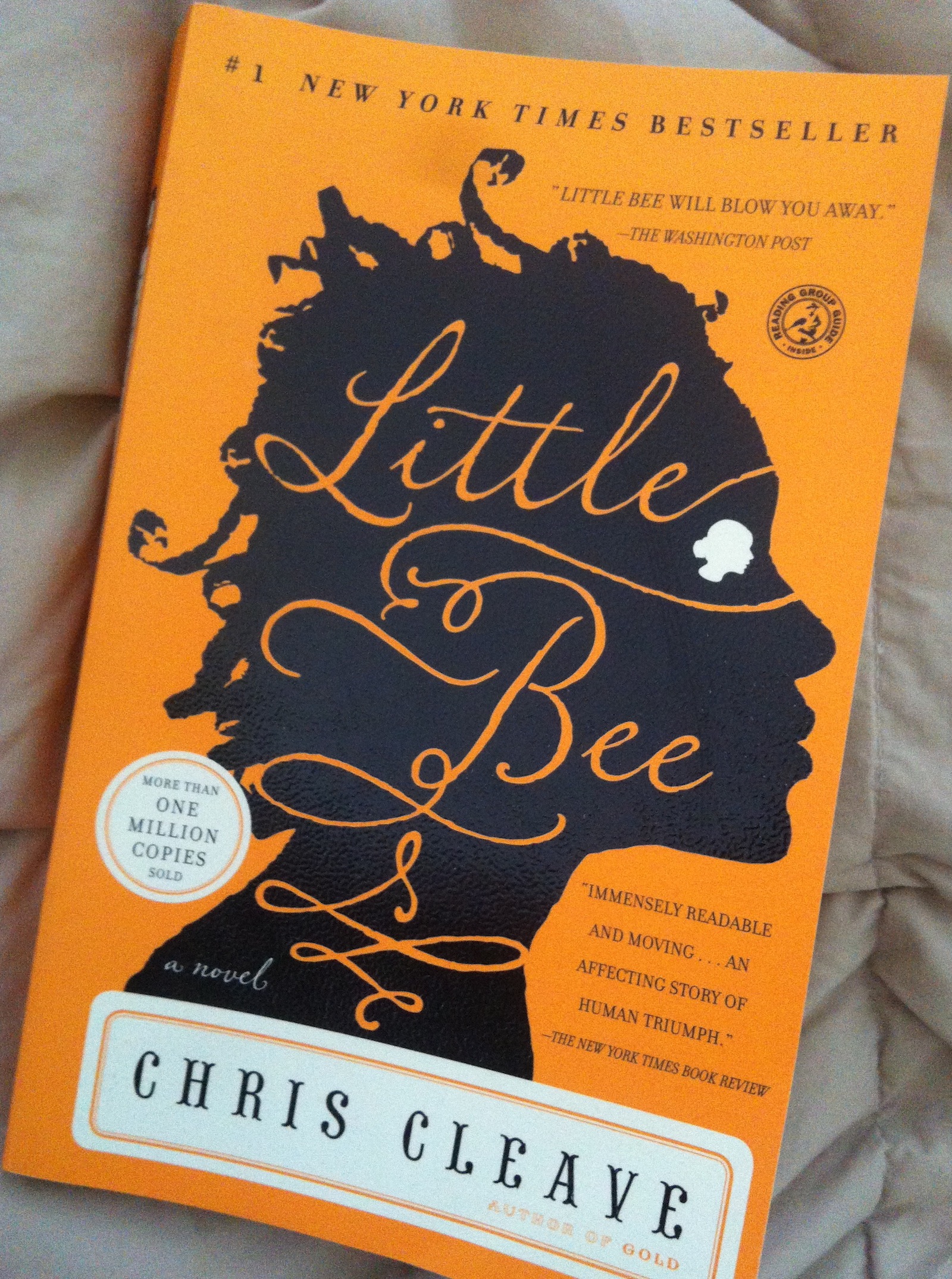

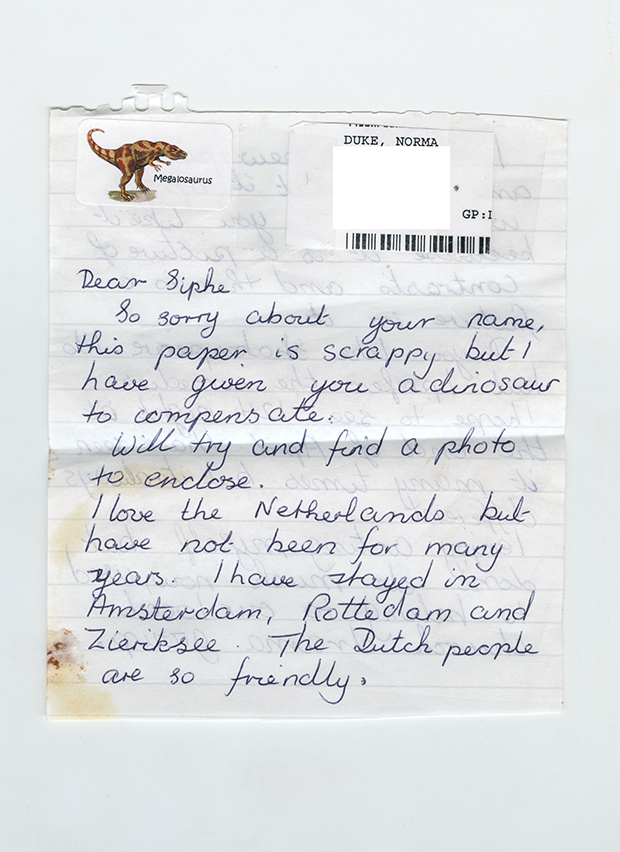

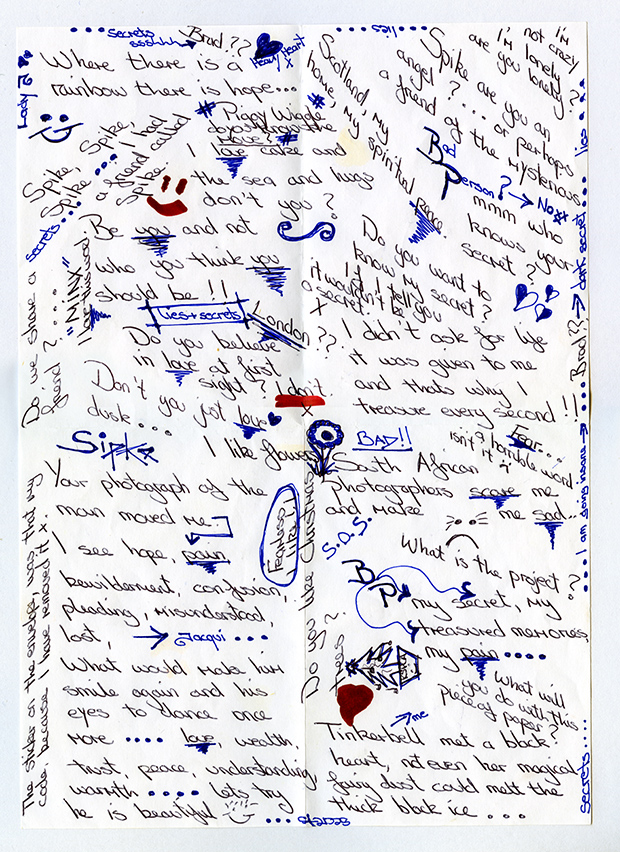

Sipke Visser grew up in the northern Netherlands, but currently resides in Wapping, London. All of his works involve strangers, and this time connecting strangers – people who otherwise would have no knowledge of the other’s existence. Sipke “aims to photograph those intimate moments when people are immersed in themselves or with each other,” and for this project Return to Sender, Sipke sent those photographs to hundreds of random addresses across the UK. Included with these photographs was a stamped and addressed return envelope along with a handwritten letter asking for a very open-ended response – either to the photograph, about your day, a random thought, anything really.

Return to Sender was recently published as a 480 page book, a careful recording of the correspondences that came from each of the 500 letters that Sipke sent over the course of two and a half years. He found the addresses at random on GoogleMaps, sending a few of the letters to the US as well. A random human response survey that allows for any sort of reply, using what’s almost now an archaic form of communication – although it is the only one that still remains somewhat physical.

This post contains images of the photographs sent and letters received, courtesy of the artist.

Did you ever have a pen pal when you were little? Do you often used the postal system to communicate with people, even if it’s just for the novelty of it?

I must have at some point but to be honest I don’t remember at all. If my penpal from back then remembers, please let me know!

When did the idea for Return to Sender strike you? Was it always intended to turn into a book?

It was in the autumn of 2008 and I was having take away dinner with three friends in yet another friends home in Amsterdam. One of them had been a postman for a while which we were talking about and then suddenly it struck me that it would be fun sending images to random strangers. The foreword in the book is written by one of these friends, the one who used to be a postman.

Which responses did you like the most? How often did the responses mention or relate to the photograph you’d sent them?

The one that stands out most is Norma since we kept on writing. There are many letters written by both of us to each other on the book. She writes about everything that happens to her. About her children, her grandchildren, her mum (who passed away at some point). I

write about what I do, my love life, London, etc. There is a guy called Donald who sent me pictures of himself and his sun. There is a beautiful one of a lady whose mother in law is not doing very well but who is very religious. The image she received happens to be religious and she writes how special that was for her. There is an A4 full of doodles by someone anonymous. And also some very rude or aggressive ones that are quite funny once you get past the rudeness – although I was a bit offended when receiving them.

Some people do talk about the image they received, but many others don’t.

What do you hope the readers of Return to Sender take away from both the book and the project as a whole?

For me it was about many things but I think the main thing is the idea that complete strangers receives a letter and a photo in the post without expecting it at all. And I’m so curious to where they ended up and I love receiving post and finding out. I think I just hope people will enjoy reading the responses and perhaps like the pictures. It’s a book you can open up on any page and since it’s a lot of pages you might find something new many times.

What other sorts of projects have you done previously and what do you think you’ll do next?

A few years ago I was very busy with work (I make most of my living as a retoucher) and barely had time to shoot so I thought it would be a good idea to invite people to my place to photograph them for an hour or so. I put an ad out on a website called Gumtree which I think is similar to Craigs List. Over 30 people visited me in about a years time and I took their portraits. The images and some text are on my website. I also once rented an empty room for a month and invited strangers over for an hour. All that was in the room was coffee, tea, an old 35mm camera with one lens and me. The light in the room was terrible and the pictures not great but it was a great way of spending time with a subject and a camera and nothing else. And I’ve got a great number of projects in my head that I want to do now, but I’m not saying what yet. The best way to stay up to date is to visit www.asortofdiary.com

{About A Sort of Diary: the website Sipke started when he moved to London from Amsterdam in 2005 to start a life in photography. A Sort of Diary is a visual outlet for what has kept him busy over the years. Not quite a blog, not quite a website, more a …. sort of diary. His eye for a great off-beat moment, combined with humorous comments and observations on the friends, family and strangers (not to mention animals) in the photos leave you feeling as though you’ve come to know him personally.}

For more of Sipke’s work, see his website.

Aug 19, 2012 | books

I’ve been thinking about opening this blog up a little – since there are so many more beautiful things out there besides painting and sculpture. So welcome to the first post in my weekend series, Art Elsewhere, where I’ll begin with stories and songs that express the beauty of the art this blog is usually about, and then move towards the stories and songs that can be considered art all by themselves.

|

| “This morning, going against all convention, I turned right instead of left.” |

The first fine art mention comes from a book of short stories I’ve been reading by the American essayist Sven Birkerts. His family is Latvian, a fact pretty tied into most of the book, and the longest story only lasts about 10 pages. They’re mostly just short, descriptive little anecdotes or memories that somehow get stressed to have a grander meaning at the end. I like them because they’re so short, and because his sentences run long with description. This excerpt comes from a story in his collection The Other Walk, called “Grandfather’s Painting,”

My hesitation makes it clear that I am no expert in the terminology of painting, though that didn’t stop me just the other day from launching into a long aside in a writing workshop comparing the essayist’s notion of a narrative destination to the painter’s marking of that point on his canvas. Here on the canvas the eye is drawn ineluctably to the small reddish-orange oblong, and it happens to be the only trace, in a world otherwise just land, sky, and water, of human presence. Was this a formulated idea? I don’t know. I never think of painters as intending things in quite this way, and to be honest, the possibility that Mike [his grandfather] might have come to it by way of an idea rather than by pure visual instinct slightly disconcerts me. It wars with the sense of his character – who he was – that I had as a child.

The painting, two feet by three, is signed M.A Zvirbulis in the lower right corner and dated 1960. As he died the very next year, it counts as one of his last. I took possession of it long after, when I began to live away from home – it became part of the very minimal decor of my life. No doubt that’s why those colors and hazily rendered shapes are so utterly familiar. I have stared and stared, often without knowing I was staring – which is maybe the real penetration. The landscape hung on nails in the living rooms and bedrooms of so many different apartments before ending up here in our house, where it has sidled from this room to that, finally mounting the dark stairs to come to rest against one of the attic bookcases. This is temporary, I say, and at some point I will give i its right new situation. But the temporary positioning also serves it: for I notice it several times every day when I come up to the attic to work. I mark its glow, or the bit of flat blue that is the lake, in a way I wouldn’t if it were to fall back into bewitched slumber on some wall. To be seen a painting has to keep announcing itself; it needs strenuousness, a way to stake its claim over and over. This landscape does many things – to me anyway – but it does not exert itself. Rather, it gives way to the gaze, subsides into itself; it makes no pitch about the world except, unadventurously, that it is. But I don’t mind. Again and again I contemplate a beautiful vista painted by an artist who loved the look of the world but was also tired, a man for whom seeking serenity had become the first priority.

|

| My dog Ollie:) |

Email me if you have any suggestions for upcoming Art Elsewheres – and happy Sundog!