Jul 29, 2013 | interviews, music

A couple of years ago, five kids met at New York University and started making music. It started as random sessions fueled by cheap wine from Trader Joes, but eventually they started recording and perfecting, drawing on influences from all over to create a serene yet deliberate experimental sound.

Melodies build on the beat as scattered voices sing out in Hindi, each song its own journey, taking the listener to imaginary exotic places. Jake Baxter, Nick Fraser, Henry Ott, Mike Hickey and Francesca Loeber make up the 2F Collective, and the group posted their first incredible album, “Wedding,” on SoundCloud this month.

Take a listen and get to know the people behind the sound in an interview Mike and the rest of 2F:

Where does the Indian feel in your music come from?

Over the last year we’ve found a few hundred vinyl records on the street, and some of our favorites were Hindu devotional records and Bollywood soundtracks. We aren’t necessarily trying to go for a heavy Indian vibe, but the samples from those records were really inspiring and lent themselves well to the sound we were trying to create.

How did you guys come up with the name the “2f collective” and which band members do what within the songs?The name originated during a failed satanic ritual. Nick plays strings and synths, Jake plays drums, Mike sings and plays guitar, Henry plays guitar, and Francesca sings. All of us are always searching for new samples and often use field recorders to collect sounds that we hear throughout the day. Some songs are written by one of us, some by all four of us, but everyone ends up contributing something to each song. Sometimes that means adding an instrument or a sample, other times it means changing the arrangement of the song. We all work together on the mixing and mastering of each song.

What’s the story behind your album artwork for Wedding?

We asked our friend Morgan Sitzler to do whatever she wanted for our album art. She was around our apartment for the entire process, from recording to mixing, and it seemed appropriate to have someone so close to the album’s musical composition take care of the visual aspect. Earlier this year she did the artwork for Henry’s Yantra EP (http://henryott.bandcamp.com/) and nailed the feeling of those songs so we felt confident that she would be able to do the same for Wedding.

Why did you name your first album Wedding?

We were listening to an old 78 vinyl of Mike’s grandparents’ wedding and the record started skipping in a really cool rhythmic way. Luckily we were recording and captured it. You can hear this at the very end of the album with his grandmother repeating “do until death.”

What’s the next step for 2f?

We’ve already begun work on a second album, and are rehearsing the Wedding songs live. We’re also doing mastering for some friends’ albums, Nick is DJing in NYC, and Henry is collaborating with a friend on a concept album called Apeman 3000.

Who are your all-time music idols?

Jake: I’ve had a few great percussion teachers over the years who opened my eyes to all types of world music. But to name a few artists, Shlohmo and Lizst.

Nick: The musicians who have had the biggest influence on me are Boys Noize, Nujabes, Shlohmo, Duke Dumont, Erol Alkan and Boards Of Canada. There are so many great artists Id love to mention who mean a lot to my song writing and DJing but I don’t want to bore you guys.

Mike: Bonobo, Wolfmother, Paul McCartney, D’Angelo

Henry: I listen to Frank Zappa, Sun Ra, and The Books.

Francesca: Beyonce, Barbara Streisand, Yukimi Nagano (Little Dragon) and Nujabes. They’re each so deliberate with every little detail.

What sorts of routines do you enact for making music? Are they different for recording versus just practicing?

Jake: I do something musical every day, either sampling, mixing, or composing. I’m working part time in a water store, which gives me a lot of free time to try out new ideas. My process is pretty consistent whether I’m recording or practicing.

Nick: That totally depends on what I’m doing. When I’m practicing or recording myself DJing, it’s a much more solitary thing because it’s just me and it’s all on me. I generally try to get really in the zone for that. Where as when we are rehearsing as 2f, it’s a much more relaxed thing because we all live together and are very close. Everyone has a lot going on so it’s really nice when we actually get a chance to rehearse together. We try to keep the mood really light, a lot of joking around and a few drinks. When we are recording it’s really much more of an anything goes sort of environment. We all trade roles of performer and recording engineer in the studio we have rigged up in our apartment. We also spend hours listening to records together looking for samples.

Mike: Usually I start with our records. I’ve been slowly going through every one picking out the parts I like, and organizing them by instrument. So typically I’ll look through my sample library to find one that I think can carry a song. Once I’ve got the main element I start making drums and then fill in the song with more samples or field recordings.

Henry: Adjusting to the way we compose our music with 2f required changing the way I make music. Rather than rehearsing the way a traditional band would with instruments, it requires constantly listening for cool sounds in your environment and recording them and sampling them. Making tracks in this mindset on a daily basis, and constantly working on each other’s tracks, is a large part of our sound.

Francesca: I don’t really have a routine. No matter what I just have to prep myself to be open to whatever I’m feeling and allow it to influence the groove

Where do you think the future of experimental music is headed? What do you want people to know about it — either the genre as a whole or 2f’s music specifically?

Jake: Experimental music to me means combining disparate elements into something cohesive. As the genre evolves I see artists weaving stranger and stranger pieces together. As for 2f, we’re trying to move towards a more satanic sound.

Nick: Kind of like experimental music in general, 2f is constantly changing because of all of the influences we draw on. It’s always what we are feeling at that time, which always changes. That way we are more free to explore ideas and move on instead of getting boxed into one way of doing things or one mindset. So you can expect some of the same stuff, but also a lot of new and very different things, and I imagine that is true for experimental music as well, although who is to say really.

Mike: That’s tough for me to say because I don’t really keep up with the current experimental scene. But in general I think experimental music, as opposed to more conventional music like pop and rock, relates more to the way people experience sound in the world. Sound doesn’t normally reach us as neat and tidily arranged sections of predictable timbre and energy, so I think it makes sense that music sometimes reflect the unpredictable flow of weird noises that we perceive every day. For 2f, I’d like to see our music spread across as many styles as possible and try to touch on as many vibes as we can.

Henry: I hear a lot of people around me coming up with new and interesting sounds that could all fall under the category of experimental music. So that gives me hope that there’s some great music being made.

Francesca: The experimental part is most fun. It basically means we have no idea what were going to do until we do it. It’s just like creative and in the moment. The relationship between all the layers is probably the most important part.

For more from the 2F Collective, check them out on SoundCloud, Bandcamp and Youtube.

Jul 19, 2013 | interviews, photography

Sarah Rosado uses dirt as a medium, perfectly molding piles into compelling shapes. Each design seems to play with the fact that the material it’s crafted from comes from the ground, either morphing into plants and animals as natural as the ground itself, or running the opposite way and becoming objects of pure human-made materialism. Her work is so whimsical and clean, the mulch laid is against a pure white in contrast so sharp it’s harmonic.

Sarah’s artistic creations started with pencil on paper, but quickly turned digital and now she works in photography as well as design. All of her work emphasizes keeping all types of interpretations open, so that each image can mean as much as possible.

Read what Sarah had to say about her work in the interview below!

Where do you get the dirt you use in your photographs?

I get the dirt for my photographs by scooping dirt from the ground in the parks.

For you, what is it about dirt that makes it the perfect medium to create from?

The challenge to me is tossing this pile of dirt on the table and bringing it to life by carefully shaping it into the selected object. It’s a great medium as the dirt sways anywhere you take it. Of course, it’s not easy, it takes practice and having the artistic skill to draw is helpful in maximizing the output of the image.

How much of the creation process happens after the photos have been taken, and how much of it happens before? (do you make the shapes perfectly out of dirt or edit the shape to perfection digitally later?)

The creation process is uniquely custom made. Everything is handmade using different tools to obtain the desired shape and accessorizing with items found around the house. After that’s done the photo is taken. There is no cropping, or digital enhancements before or after. It’s all real.

What’s your favorite (or a couple of favorites) photograph you’ve created? Who are your art idols?

My favorite photographs are the smoking revolver, little duckling and the tuxedo which I had lots of fun creating. It’s hard to choose a favorite among so many great artists.

See more of Sarah’s work on her website.

Jul 8, 2013 | interviews, music

Simple melodies that build behind pure voices is music that’ll make you homesick. The Novel Ideas’ third album is called Home for a reason, with sweet lyrics about being alone and growing up, about remembering who you used to be and the people who helped you become the person you are now. But instead of a melancholy sound that laments the lost time, each song on Home has its own sweeping, bouncing rhythm – a soundtrack for memories, reunions and old times.

They describe themselves as a “folk rock outfit of friends” – Daniel, Danny, James, Sarah, Nick and Ezra. Last year the group recorded Home amidst the elements in a New Hampshire barn. Daniel, on guitar and vocals, was nice enough to answer a couple of questions about what it takes to make memory-filled music:

How did the six of you meet, and when did you first find out that you could make great music together?

Danny and I met in kindergarten, James and I met at Boston College. We met Sarah via Reddit. And Nick joined thanks to our Craigslist ad looking for a drummer. We’ve been working on new songs as a band and I can say that it is much more fun and successful than trying to work out songs while recording them.

What was it like recording “Home” in a New Hampshire barn?

Recording in New Hampshire was a really nice outlet for us. It was a rough summer in a lot of ways and having a place of respite to focus only on music was really nice. We’ll be recording some of the new album in the same barn which will be fun, except for the bugs.

Which band member writes the songs, and where do the lyrics originate?

Myself (Daniel), Danny and Sarah write the base of the songs but the songwriting process has been very collaborative. James is excellent at writing bass parts and has an amazing sense of harmony, while Nick has a knack for rhythm (naturally as a drummer) and song structure. Said simply, our lyrics originate from the experiences we go through. Some are sad, some are happy, some are bittersweet. Personally I find it impossible to be content writing anything I don’t feel is completely true, so writing honest lyrics is especially important to me.

Which songs on Home do which vocalists sing, and what do you think the different voices offer your music?

Danny and I are the only lead vocalists on “Home,” though Sarah and James are also both featured on the record. Some of my favorite bands have multiple lead singers: (ex: The Beatles, Fleetwood Mac, The Beach Boys…) I think it can add a whole new dimension (or two) to a band.

Who are some of your folk idols, and how do you guys keep your own sound unique?

I know we’ve all been listening to a lot of Sera Cahoone lately. Her melodies are absolutely beautiful as well as her pedal steel parts (which we’ve been trying to steal a page from). Kathleen Edwards is also one of our favorites. I suppose in terms of trying to keep our sound unique, it comes from having many different influences. Some days I feel like listening to Bon Iver, some days Gavin Bryars, and some days Taylor Swift. I suppose our music comes out of five people’s different tastes and styles but with the intention to create a common and unifying style.

A lot of your songs are quiet and happy with melodies that rise and grow. What sort of experience are you trying to create for the listener? Where do you try to bring them with your music?

When I write a song I want the listener to understand and even feel the things that I felt while I wrote that song, and feel what I feel when I sing that song. If I can impart that through my music I’ll feel I’ve connected with others in a meaningful way.

Promise is one of my favorite songs on the album, with lyrics that start like this:

Here we are now in the backyard

On the warm ground out at sundown

But in twelve days I’ll be halfway

Cross the world, I’m too tired to be afraid

You’ve got green eyes, I had foresight

When I said we’d be good I was so right

If we lay here, spend every day here

Well our legs might take root and we’ll grow dear

I made a promise to you

The Novel Ideas will be performing throughout July and August, with one show in Providence and three in Massachusetts.

Get tickets here, and check out the band’s Facebook page or their website for more information.

Apr 24, 2013 | art history, interviews

Ben Street is a freelance art historian, writer and curator based in London. He has lectured for the National Gallery for many years and also lectures for Tate, Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Saatchi Gallery and Christie’s Education. Ben writes for the magazine Art Review and has published numerous texts for museums and galleries in Europe and America. He is the co-director of the art fair Sluice, and has curated a number of contemporary art shows at galleries in London. More information can be found at www.benstreet.co.uk.

Ben kindly answered some questions about how he got to where he is, and what it’s like to share art professionally in pretty much every way possible. He works with art that spans centuries, lecturing in the halls of prestigious museums while curating and covering contemporary art for modern magazines and galleries.

How did you come to realize that studying fine art was what you wanted to do with your life? What is it about art that makes it worth your dedication?

I got into art by making art, which I don’t do any more (at the moment, at least, to the great relief of many of my artist friends). Through painting, I became interested in various painters (Bacon, Grosz, Beckmann, people like that – I was a teenager, obviously). I remember seeing retrospectives in London of Picasso and Pollock, and the New York Guggenheim’s big Rauschenberg retrospective, which sparked a fascination with twentieth-century art, and I came to older art much later. (Initially I found it – older art, of the Renaissance and so on – incredibly difficult to grasp, which is the opposite way around to how it usually works). I can’t quite work out what makes art worth all this time, but I can’t stop spending all my time on it. I never feel like I know enough, that’s the motivation. Even paintings I’ve seen literally hundreds of times, and have written about and researched extensively – I feel I barely know them, which is an exciting feeling.

Can you remember the first work of art that had a really deep, profound impression on you?

I don’t think early experiences of art are really about deep and profound impressions. They’re about a gradual and insidious seeping into the subconscious and slow possession of the psyche, like an anaconda slowly suffocating a missionary explorer, and once you realise it’s happened, it’s too late – you can’t wriggle out again. I didn’t see that much famous art until I was a teenager, and even then it was mostly in books or on postcards. Consequently I have probably a deeper relationship with reproductions than with ‘real’ works of art – I have a sneaking suspicion they can be just as good as the original thing.

How does your knowledge and experience in lecturing play a role in the curation process for new work?

I have no idea – in fact, I’d try and avoid any crossover there for fear of being didactic. The worst curatorial policy begins with a theme and seeks works of art to illustrate it. Although I’d like my teaching/lecturing to be more about facilitating conversations between works of art across history, which is my idea of interesting curation, rather than regurgitating all the facts I’ve read, which is my idea of bad teaching.

Would you consider yourself an “art critic” at all? What does an artwork need to lack or have for you to absolutely hate or love it?

Yes, because I review exhibitions for Art Review magazine. Every really good work of art sets its own criteria by which it should be judged. There isn’t a universal measure, in other words. This is true of Titian as much as it is of Donald Judd, Matisse, David Hammons, or Duccio, to name a few artists I’ve been pretty obsessed with recently. It’s about a certain kind of force which obliges you to reassess what you thought you thought. That force is not dependent upon scale, or historical period, or medium. You know it when you see it – like pornography.

Whether lecturing or writing, how do you gauge the appropriate style that will reach the audience most effectively? Do you base it on their level of knowledge, assumed interests or something else?

I’d like very much to communicate ideas in a clear and comprehensible way, without compromising the complexity of those ideas. Sometimes that works and sometimes not. I’m very much in favour of encouraging people to look closely at works of art, and to be prepared to work hard (thinking, looking, analysing, discussing) to reap the big rewards. Looking has to be active and thoughtful and switched-on, but our world conspires against that: we see more images than ever, but our seeing has become passive – images require giving, not just receiving. Works of art are like gyms for the eyes, and once you start working out – stay with me – your life will be enlivened in a quite amazing way.

For more from Ben Street follow him on Facebook and on Twitter.

Mar 29, 2013 | interviews, painting

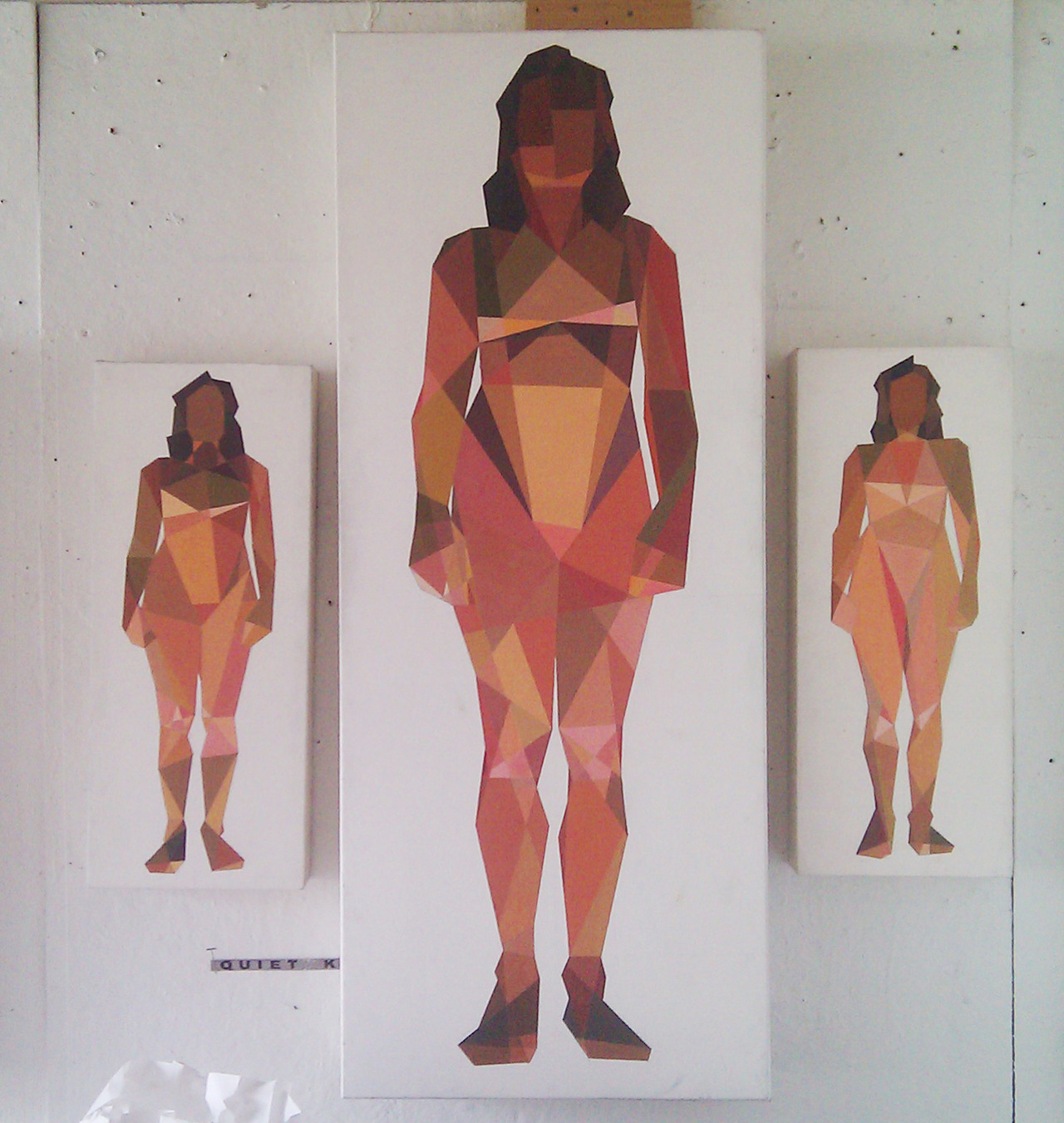

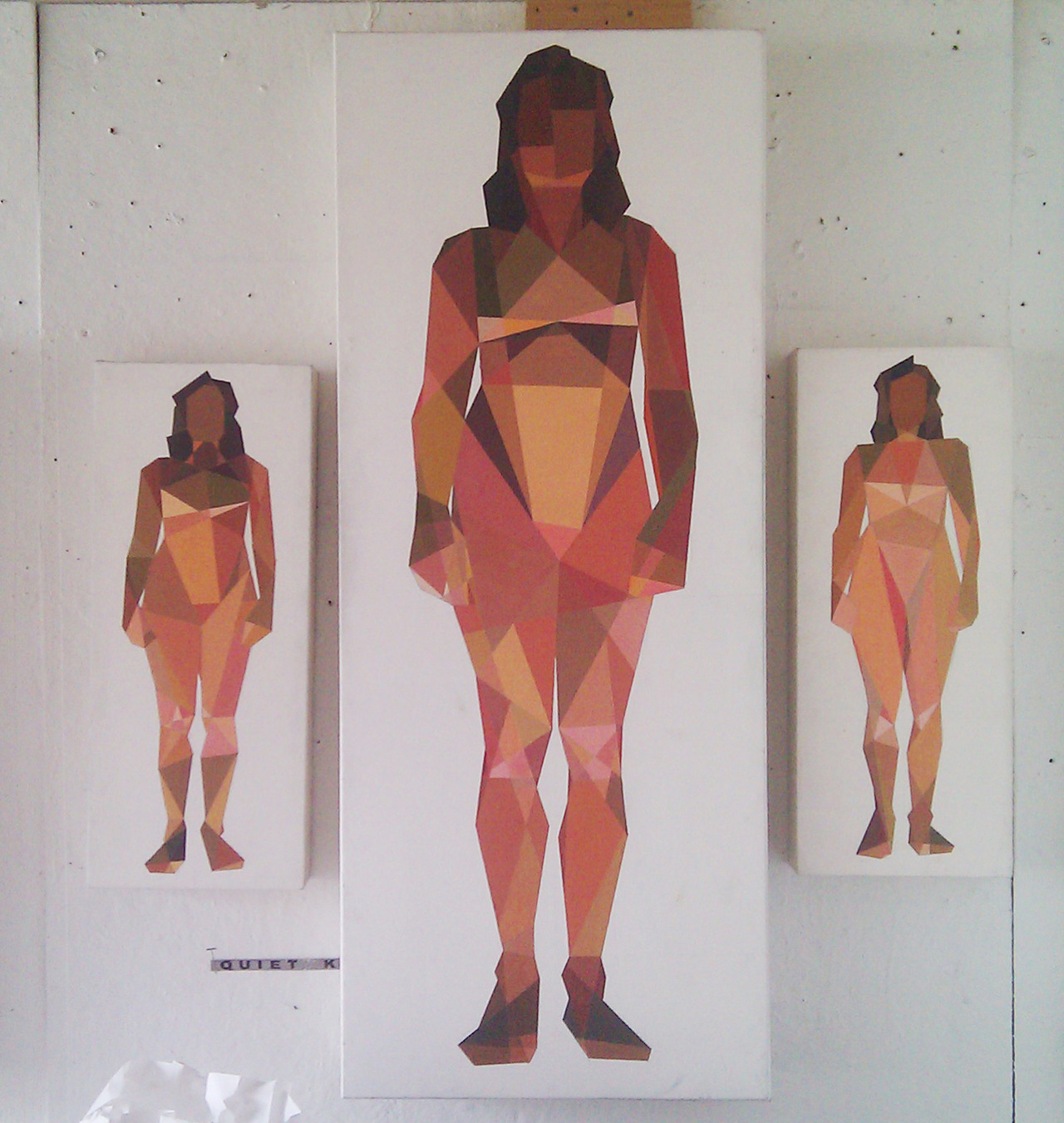

The women in Ian Gage’s paintings have recently begun transitioning – changing from realistic women splashed in dark paint to geometric pixillations that fragment her body and surroundings. The result is a shattered representation of women like minimalist stained glass windows, the light shining off of each shape differently, and with her body arranged in sometimes symmetrical but always balanced compositions.

Toll, Knell, & Peal reveal three different interpretations of the same front facing woman, and in each, her body is shattered into different shapes shaded in different shades of light. The transition between Ian’s realism style and his fragmented one can be traced from work to work, like a breadcrumb trail of the artistic process. Scrolling through his Tumblr is like reading a mystery novel where all the clues are visual, connecting the works that come before and after.

Cease and Knell shown at the Sustain/Able show at MassArt, 2012

What is the first thing you can ever remember drawing?

I think Godzilla. I was pretty preoccupied with typical giant robot/creature type products as a child—typically referred to as kaiju, though I don’t usually throw around that term. A Google search of that pretty much sums up the things I drew as a child.

Toll, Knell, & Peal

To you, what is it about women that make them so worth painting?

The anecdote I usually dispense as an answer for this is that I only took up an interest in drawing in response to a middle school crush. The crush in question was very interested in art and I pursued it to impress her. She moved away and nothing ever came of that, but I kept drawing. Ever since that point I’ve been interested in drawing or painting my romantic interests—it’s fairly transparent at this point to the people close to me.

I think there are a lot of things about painting women, in particular romantic interests, which one has to be cautious about. The first thing you hear in art school is that portraying someone you’re close to inevitably leads to an idealization complex—you’re never really able to accurately portray your subject because you’re occupied trying to flatter them. I’d like to think I’ve broken that barrier based alone on my obsession with proportionate accuracy, but one can never be trusted to judge themselves objectively. I can at least say in my defense that no one has mentioned idealization critically to me for probably two years. The second—and more broadly relevant point of caution, is my position as a male painting the female form. After seeing a Hilary Harkness lecture this past fall I grew somewhat uncomfortable with the plausibility of being labeled a misogynist based on my work, and so I try to be as aware of the presence of the male gaze in my paintings as possible. The effectiveness of that awareness can really only be judged by the female audience—I am at their mercy under the circumstances and that is the way it ought to be. Those are the two chief dangers I think.

I realize of course I have yet to answer the question, but that feels like some necessary pretext. I think I’ve always been very interested in making art about women due to their general impact on my life; it’s difficult to give an answer less nebulous than that. Painting women is something I generally don’t question, it’s just something that feels necessary, and has felt more so as I’ve gotten older. Continuing painting women, and justifying it, involves a lot of thought and deliberation on a daily basis; particularly revolving all of the implications of me painting women, and of painting women in general.

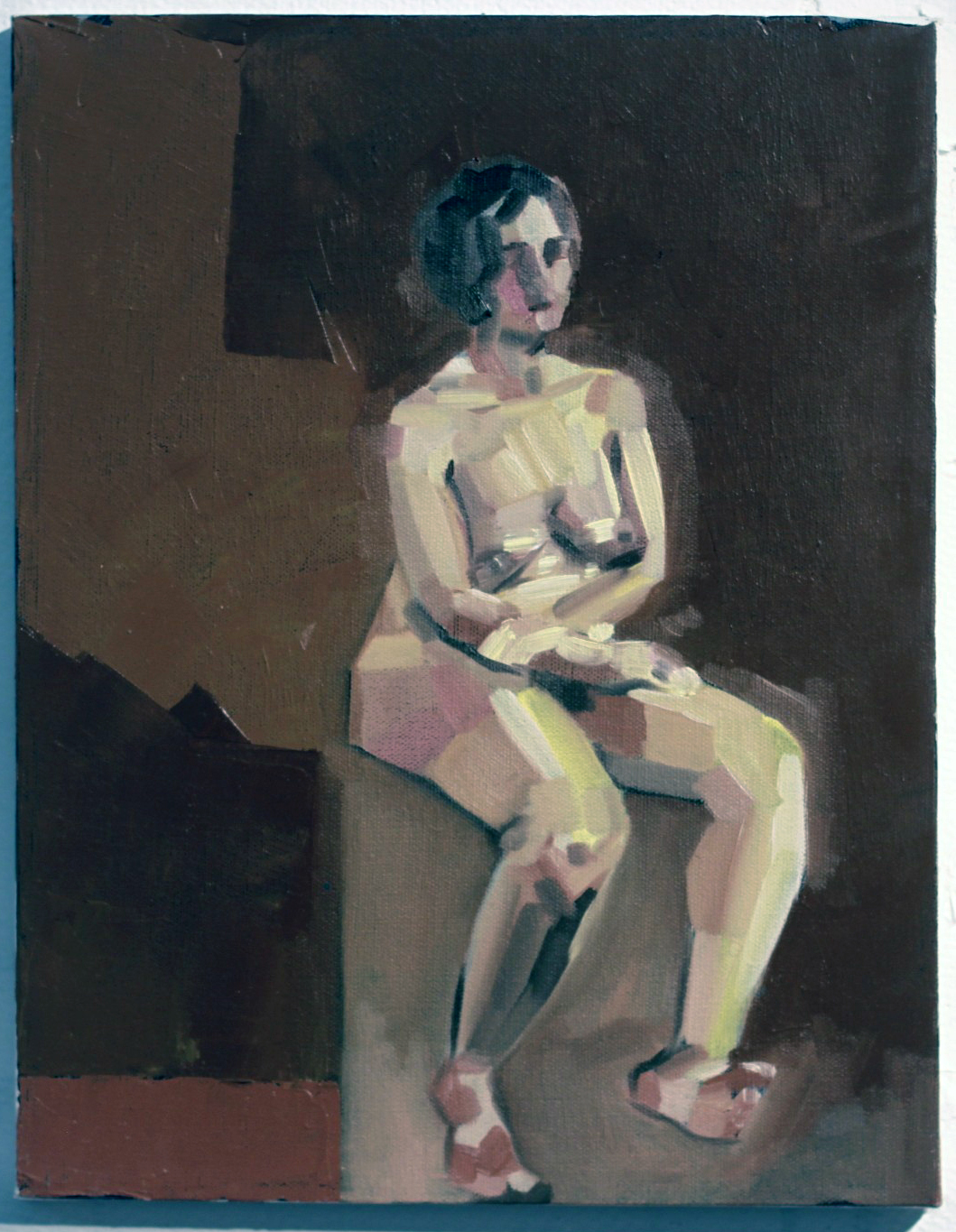

Untitled, Oil on canvas, 12”x16”

When did you first begin moving away from straight representations to geometry-inspired interpretations, and why?

I really started painting the geometric pieces in Catherine Kehoe’s representative painting class. From the beginning of the class I assumed we were learning to paint representatively (a logical assumption) but we were in fact learning the building blocks. I assumed the class structure would revolve around Kehoe giving us broad lessons on the tenets of painting naturalistically, and then individual suggestions to improve the realism of our work. I was chiefly interested in exhaustive detail—I wanted to paint like Scott Prior by the end of the class.

I found fairly quickly she was teaching the opposite of detail. Kehoe encouraged us to reduce the picture plane to the simplest shapes possible. I fiercely resisted this for about half of the semester, at which point I became exasperated and painted an exhaustively reductive study in an attempt to parody her lessons. It was absolutely meant to be a juvenile jab at her teaching, but to my surprise she loved the painting and encouraged me to pursue it further. For the duration of the class I developed a vocabulary in a style I had originally created as a joke, and grew to like it despite the fact I was painting expressive acrylic paintings in my personal studio. When I had my final critique in my painting studio the professor and guest artists were enamored of the Kehoe paintings and uninterested in my expressive paintings. That was the point at which I decided I needed to explore reductive painting more.

Untitled, Acrylic on canvas, 12”x16”

How would you describe the differences between those two styles?

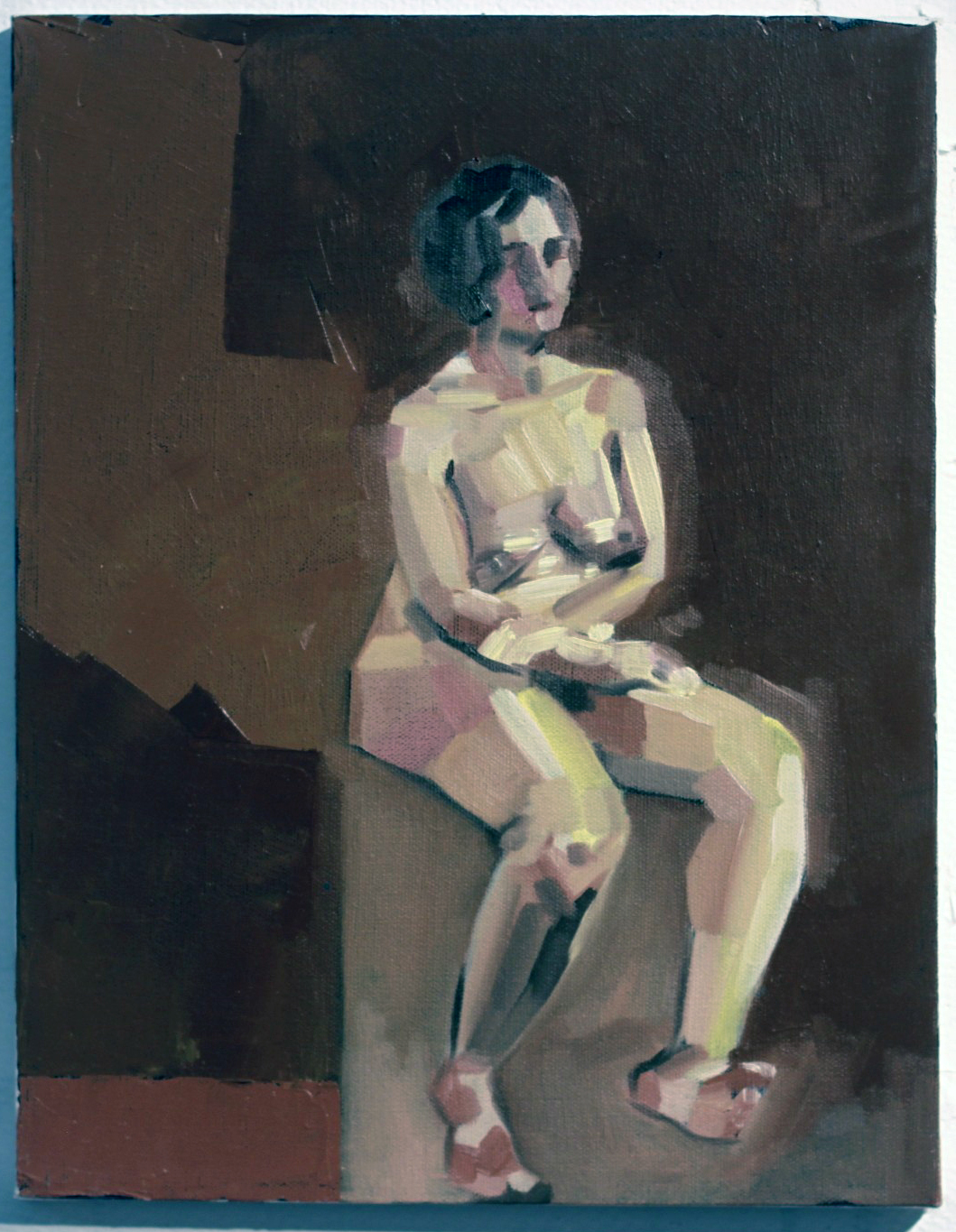

Per the usual tortured artist criteria: I was in an emotionally turbulent point in my life for about a year, during which I lacked a single subject to paint. During that year I was really painting self-portraits with other people’s faces—I wanted to paint women but really just wanted to paint what I was feeling. That kind of expressive venting was the source of the majority of the imagery in that period of painting.

In a sort of coincidental windfall I was transitioning to painting geometrically when I met my current girlfriend, who is the subject of all of my paintings since that point (about a year now). In my personal life I moved into a more stable place, and my paintings became a lot more stable too. I think under these circumstances the primary difference is that the older paintings are very expressive and energetic; I was clearly being very physical with the works, and the current paintings are more analytical. I’m interested right now with proportionate accuracy, the dynamics of different geometric hierarchies, and color theory. Succinctly, the difference is expression vs. study.

Seated Nude #3, Oil, Acrylic, Graphite on Canvas, 8”x10”

Who are these women? What do they represent to you?

The current paintings are all of Melissa, my girlfriend. Most of the older works are of Emma, a friend. The Emma paintings really fall under the self-portrait category, they’re about me at the time if anything. There were a couple of early Melissa paintings that fell under that category as well, namely Seam Ripper and Discrete Mathematics, after which point I dropped the expressive self-portrait vein for the reductive paintings.

The reductive paintings are a lot less about expression and more about study. Every painting is an attempt at adding or manipulating a variable in a previously established control. When something works I add it to the control; I add it to my toolbox. When it doesn’t work it remains exclusive to that painting. For instance: the blank figures in Seated Nudes 1 & 2 were an accident—I had placed a red ground, drawn the space, and painted the backgrounds. I decided before I painted the figures that they looked interesting as they stood, and left them. The silhouetted figure became part of my vocabulary at that point, and it reappeared in later paintings.

As far as what the women in the paintings represent to me beyond the above technicalities, I can’t really say. I try not to assign meaning to my paintings; I find I’m opposed to explaining the content because it places the painting in a box. A painting is infinitely more valuable to the viewer when they can assign their own meaning to it or attempt to glean the meaning themselves.

Reclining Nude IV, Oil on canvas 12”x12”

What sort of impression do you hope your works leave on the viewer?

It’s difficult to say based on the above statement. I hope it strikes a chord with them, I hope there’s something in them that they can take away. I hope they want to spend more time with it than five seconds.

[pureslideshow] https://thingsworthdescribing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/gage8.jpg;https://thingsworthdescribing.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/gage7.jpg; [/pureslideshow]

Ian will be graduating from Massachusetts College of Art and Design this spring.

See more of his work on his Tumblr.

Mar 8, 2013 | interviews, painting

“Moving in with Richard Diebenkorn”

Alexandra Rozenman is an artist now living and working in New England after coming to America as a political refugee from Moscow at the end of the 80s. Her paintings reveal simple scenes of beauty and most often peace – a utopia so perfect that it could only exist within four walls of canvas. Her new show, “Transplanted” continues her exploration of scenic storytelling, using color and shape to serve as a narrative for each viewer to interpret on their own.

“Moving in with de Chirico”l art

What was the first thing you can remember painting?

I started painting when I was 5 taking classes at the Fine Art Museum in Moscow. There is a photograph taken at the dacha that my parents rented in 1977 for the summer. I am sitting at the easel looking very serious. Painting on an easel tells a story the same way my work does now: there is a house in the woods and a fairytale character: Petrushka ! ( Petrushka is a stock character of Russian folk puppetry, known at least since 17th century). I would not be surprised if I found out about him from a Stravinsky ballet that has the same name, because may be there was not always paper, but the theater was affordable, wonderful and available. This painting has two big eyes in the sky – one of the images in my work for the last 20 years.

Do you have any routines required for the creation of your work?

In ideal world I prefer to work in the morning after 2-3 cups of strong black tea. Afterwards I eat good lunch and have a nap! Then work for 2-3 hours more. I like to feel alienated when I work. I like listening to a very loud music (something nobody will guess I do). With the schedule I have right now ( I started my own private art school www.artschool99.com) and am teaching almost every day for 5 hours or so). I am trying to cut out pieces of time for myself and just make it work. A tight schedule became one of my art materials:)

“Moving in with Leonardo”

How do you find the right color scheme for each scene?

I don’t think I find the right color. I allow colors to find me. Paint floats and has its own mind based on subject matter, technique, materials, time, space. It is alive for me and my goal is to allow it to grow up (like a plant) and only later – some time in the middle of the painting process – start changing it, based on my instinct, ideas and goals. Each painting is different.

Where do you hope to take the viewer with your paintings, and why?

I tell my viewer a story, allow them to enter into the world of magic and hope that they will get curious and will spend some time thinking and looking around. My work expresses longing for understanding and being understood, for non-belonging and finding a place to be. Playfulness in my work points to instability of life – visually, culturally and literally. I am working playing on the conflicts between identity and assimilation, tradition and modernity, so each viewer can take my messages and interpret them any way they want and discover for themselves. I want the viewer to start wondering after looking at my paintings, if maybe things are a bit different sometimes, maybe something can still be both beautiful and interesting at the same time.

“Moving in with Winslow Homer”

How would you describe your style of painting?

In todays world “style” is usually a combination of many different styles, isms and personal history or/and an artists place in the world. Inside my work liquid layers and thick abstractly painted surfaces meet familiar landscapes, and create a place where I explore the world through the mixture of autobiography, symbolism and philosophy. I am a mix of Moscow alternative cultural scene of the 1980’s ( my visual vocabulary, environments, approach to a hidden metaphor are all coming from their ), Painting for paintings sake, Abstract Expressionism, New image painting, Fauvism , 16th-17th century Romanticism and Symbolism can all be found in my work.

My favorite artists are: Bruegel, Vermeer, Turner, Matisse, Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Snyder and Frida Kahlo. For many many years my work has been compared to Marc Chagall. I like his early work and am even really related to his first wife (Bella Rosenfeld) – my Great Grand father is her younger brother, but I don’t think that he is my main influence. However, if there is a group of artists called “Jewish Artists” I am sure I am a part of it.

How does “Transplanted” expand upon the styles and themes your work has already been exploring?

For me “Transplanted” has a seed of placing myself in the world of art. Thoughts and practice on what it is to be a painter in the 21st century. Saying that replanted artists, immigrants from the disintegrated homeland, like myself, survive against all odds

And, kind of a random one: what’s your favorite color?

I don’t think I have one favorite color. I love color. It depends on what it is for. There is one color that I strongly dislike: pink. I agree with Matisse who said that:”The use of expressive colors is felt to be one of the basic elements of the modern mentality, an historical necessity, beyond choice.”

“Re-thinking Malevich in Moscow”

From Alexandra: “Re-thinking series was 15

years ago and is sort of a mother of ‘moving in.'”

See Alexandra’s website for more of her work.

“Transplanted” is on view at the Multicultural Arts Center in East Cambridge, MA from January 3 – April 8, 2013.