Mar 18, 2012 | illustration, Museum of Fine Arts: Boston

A sun in the center of the sky hovers above a low, watery horizon. An angel made of pure muscle seems to leap from this horizon, his back toe just resting on the edge of the water, thrusting the rest of his body with heavy, feathery wings expanded, into the center of the composition.

His whole body is twitching with motion; his hand reaches up and back to the sun that falls behind him. All limbs are outstretched and exposed, his head shot back as well, leaving his jaw lit but his face in shadow, surrounded by a shroud of whispy, curly hair.

|

| Crayon, oil, and graphite on canvas. At the MFA in Boston. |

The rest of the painting is left blank, allowing us to focus on the pose and outstretched motion of the angel, who is somehow being lit from the front even with the sun behind him. The dark weighty feathers of his wings are given details only where necessary.

His overly lined musculature is perfectly sketched in brown outline and shading before a light shade of orange was applied – the same orange added at the edges of his great wings for accent.

GD Star Rating

loading...

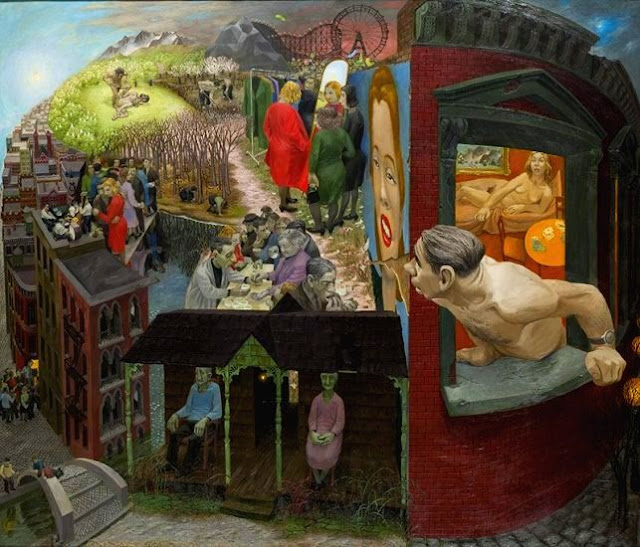

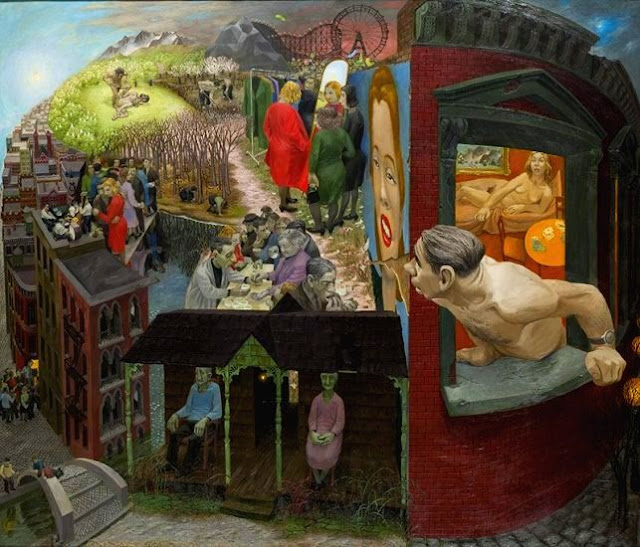

Jan 15, 2012 | painting, The Whitney Museum

|

| Oil on composition board. Whitney Museum. |

The whole image is comprised of varying scenes on one landscape, one globe, that connect in surreal, imagined ways. The street of a celebration scene leads by a warped metaphorical bridge to the front porch of an old couple colored green– they may already be dead. Over their roof leans a frumpy, middle-aged man who’s just left his very normal woman in bed to look out his window over his surely disappointing, surreally laid-out life. An unhappy dinner party takes place by a lake in the center, but the lake itself looks more like a glimpse into the underworld than a reflection of nearby trees. A nude man murders his brother in a field on the top left of this world, (very reminiscent of Cain and Abel) mirrored by topless farmers on the right. Metaphorical roller coasters can be seen in the distance, and a grotesque grayed woman examines herself in a more literal mirror while her even grosser friends look on. Really the only aesthetically pleasing aspect of this painting is the woman in the advertisement on the side of the middle-aged man’s building, but even she has a crack running through her face.

GD Star Rating

loading...

Apr 24, 2013 | art history, interviews

Ben Street is a freelance art historian, writer and curator based in London. He has lectured for the National Gallery for many years and also lectures for Tate, Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Saatchi Gallery and Christie’s Education. Ben writes for the magazine Art Review and has published numerous texts for museums and galleries in Europe and America. He is the co-director of the art fair Sluice, and has curated a number of contemporary art shows at galleries in London. More information can be found at www.benstreet.co.uk.

Ben kindly answered some questions about how he got to where he is, and what it’s like to share art professionally in pretty much every way possible. He works with art that spans centuries, lecturing in the halls of prestigious museums while curating and covering contemporary art for modern magazines and galleries.

How did you come to realize that studying fine art was what you wanted to do with your life? What is it about art that makes it worth your dedication?

I got into art by making art, which I don’t do any more (at the moment, at least, to the great relief of many of my artist friends). Through painting, I became interested in various painters (Bacon, Grosz, Beckmann, people like that – I was a teenager, obviously). I remember seeing retrospectives in London of Picasso and Pollock, and the New York Guggenheim’s big Rauschenberg retrospective, which sparked a fascination with twentieth-century art, and I came to older art much later. (Initially I found it – older art, of the Renaissance and so on – incredibly difficult to grasp, which is the opposite way around to how it usually works). I can’t quite work out what makes art worth all this time, but I can’t stop spending all my time on it. I never feel like I know enough, that’s the motivation. Even paintings I’ve seen literally hundreds of times, and have written about and researched extensively – I feel I barely know them, which is an exciting feeling.

Can you remember the first work of art that had a really deep, profound impression on you?

I don’t think early experiences of art are really about deep and profound impressions. They’re about a gradual and insidious seeping into the subconscious and slow possession of the psyche, like an anaconda slowly suffocating a missionary explorer, and once you realise it’s happened, it’s too late – you can’t wriggle out again. I didn’t see that much famous art until I was a teenager, and even then it was mostly in books or on postcards. Consequently I have probably a deeper relationship with reproductions than with ‘real’ works of art – I have a sneaking suspicion they can be just as good as the original thing.

How does your knowledge and experience in lecturing play a role in the curation process for new work?

I have no idea – in fact, I’d try and avoid any crossover there for fear of being didactic. The worst curatorial policy begins with a theme and seeks works of art to illustrate it. Although I’d like my teaching/lecturing to be more about facilitating conversations between works of art across history, which is my idea of interesting curation, rather than regurgitating all the facts I’ve read, which is my idea of bad teaching.

Would you consider yourself an “art critic” at all? What does an artwork need to lack or have for you to absolutely hate or love it?

Yes, because I review exhibitions for Art Review magazine. Every really good work of art sets its own criteria by which it should be judged. There isn’t a universal measure, in other words. This is true of Titian as much as it is of Donald Judd, Matisse, David Hammons, or Duccio, to name a few artists I’ve been pretty obsessed with recently. It’s about a certain kind of force which obliges you to reassess what you thought you thought. That force is not dependent upon scale, or historical period, or medium. You know it when you see it – like pornography.

Whether lecturing or writing, how do you gauge the appropriate style that will reach the audience most effectively? Do you base it on their level of knowledge, assumed interests or something else?

I’d like very much to communicate ideas in a clear and comprehensible way, without compromising the complexity of those ideas. Sometimes that works and sometimes not. I’m very much in favour of encouraging people to look closely at works of art, and to be prepared to work hard (thinking, looking, analysing, discussing) to reap the big rewards. Looking has to be active and thoughtful and switched-on, but our world conspires against that: we see more images than ever, but our seeing has become passive – images require giving, not just receiving. Works of art are like gyms for the eyes, and once you start working out – stay with me – your life will be enlivened in a quite amazing way.

For more from Ben Street follow him on Facebook and on Twitter.

GD Star Rating

loading...