Feb 5, 2012 | painting, The Met

.JPG) |

| Oil on canvas, The Met |

The flow and sparkle of the river spills across the entire canvas. The small naked child in the foreground has her back to us– she’s about to jump in and join her friends whose white and pink gowns are already clinging to their bodies and floating in the water. Even though the little girl’s distinct shape separates her from the dream-like scene, the same melting shades of yellow, green, and blue are reflected in her skin and in the shadows cast on it. The smallest shadow, cast by her left shoulder blade onto her back, gives her a level of naturalism that contrasts with her flowy, dreamy surroundings. Her feet are in transition, inches from the water and already blurrier than the rest of her that is to follow. She wears a red ribbon in her braided brown hair, the sole addition to her soft, glowing body. The only face revealed to us within the scene is faceless. It’s that of the white-gowned older girl, and it only further emphasizes this lake as a dream-scape– elusive and blurry, but sparkling and beautiful. The little girl’s friends led her, and now she’s leading us to the lake.

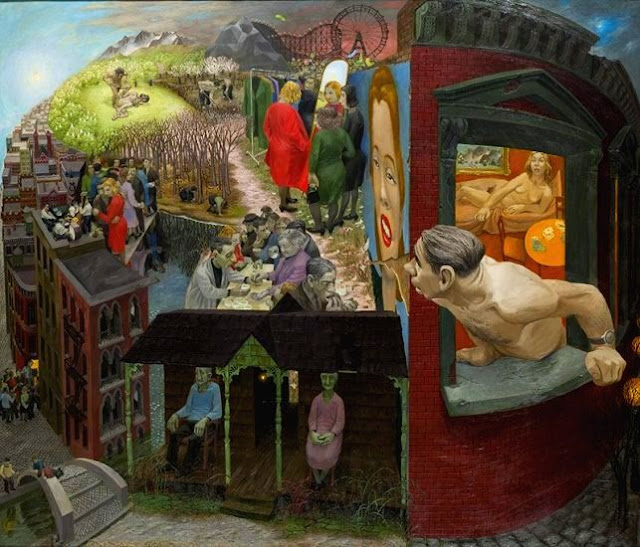

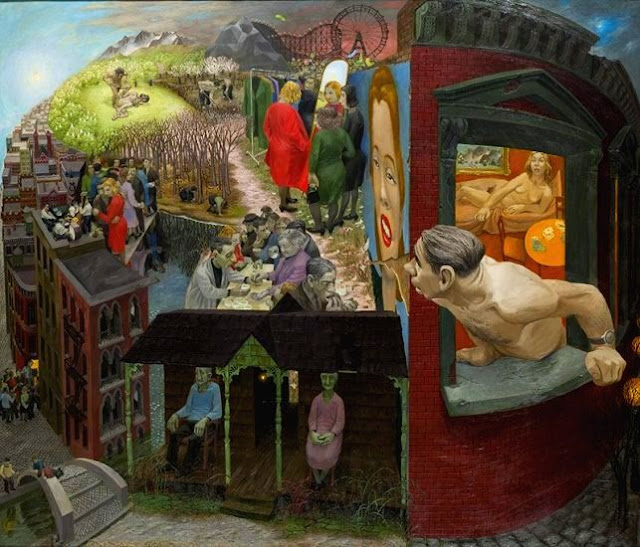

Jan 15, 2012 | painting, The Whitney Museum

|

| Oil on composition board. Whitney Museum. |

The whole image is comprised of varying scenes on one landscape, one globe, that connect in surreal, imagined ways. The street of a celebration scene leads by a warped metaphorical bridge to the front porch of an old couple colored green– they may already be dead. Over their roof leans a frumpy, middle-aged man who’s just left his very normal woman in bed to look out his window over his surely disappointing, surreally laid-out life. An unhappy dinner party takes place by a lake in the center, but the lake itself looks more like a glimpse into the underworld than a reflection of nearby trees. A nude man murders his brother in a field on the top left of this world, (very reminiscent of Cain and Abel) mirrored by topless farmers on the right. Metaphorical roller coasters can be seen in the distance, and a grotesque grayed woman examines herself in a more literal mirror while her even grosser friends look on. Really the only aesthetically pleasing aspect of this painting is the woman in the advertisement on the side of the middle-aged man’s building, but even she has a crack running through her face.

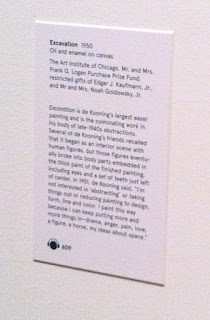

Jan 9, 2012 | MoMA, painting

|

| Oil and enamel on canvas. |

(I saw the de Kooning: A Retrospective exhibit at the MoMA this weekend:)

Because of its strategic placement within the exhibit, you know it’s a big deal. It’s at the dead center in the very back, as a way of suggesting that this is what the rest of the exhibit is leading up to. And it’s understandable why it’s such a big deal. I’ve never seen anything like it. It was completed in the same harsh, hurried style that de Kooning seems fond of, but the slashes and spots of color seem more like the result of a more methodical process. The yellows, dark pinks, turquoises, and deep reds break through the overwhelming creme/beige color in ways that both complement the colors themselves, as well as their placements on the canvas. The sometimes-dripping, sometimes-smudged, black lines that surround and seem to almost reveal these colors really does make the piece a kind of excavation. A search for color and brightness that takes a lot of harsh black and ugly beige to find. It makes me pretty proud to be wearing bright red pants as I stand here staring at it.

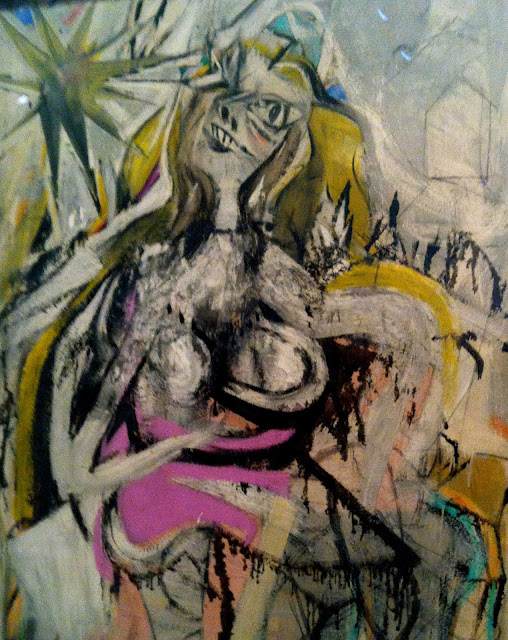

Jan 7, 2012 | MoMA, painting

|

| Oil and enamel on fiberboard. |

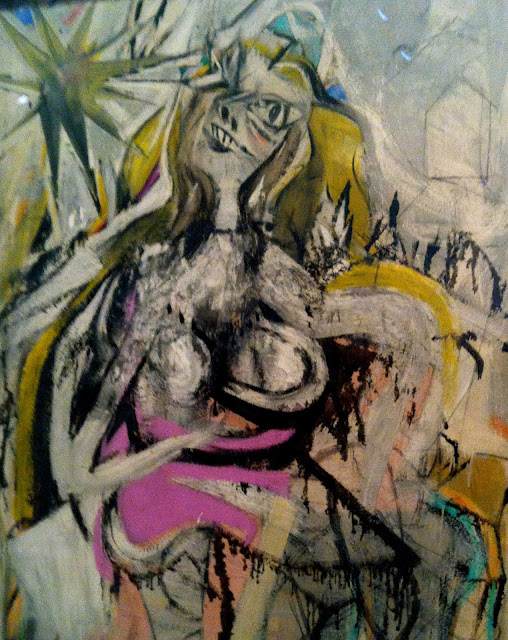

At first glance she’s almost frightening. The harsh, dripping nature of the ink outline of her dress gives the whole piece a rather crude, unfinished look. But it’s obvious by the content of the painting that it actually is finished.

The woman’s left eye is wide and cartoon-like, while her right is blurred and blinded by a huge star above her, morphing the entire space where her eye would be into a deliberate reflection of the star’s dark light. The other elements of her face are scratched out in a similarly eerie fashion, with her nose mostly nostril and her mouth mostly teeth. The empty, colorless outline of a house behind her is only background, the past, forgotten. Especially when confronted with her rounded irregular breasts magnified by their foreground presence, and bright off-putting hues of purple, pink, turquoise, and orange. The pale, sick yellow of her willowy hair mirrors the yellow of the star that she seems to be so enthralled with.

Mar 28, 2011 | painting, The Louvre

François-Edouard Picot

L’Amour et Psyché, 1817

(“Cupid and Psyche”)

It’s the morning after and the angel man is leaving her sleeping. Her arm is outstretched around where the space where he would have been, but now that space is just depressingly empty. The sun shines on her naked body and a sheer white robe lingers around her hips, flowing down across her legs. Her face is upturned, peaceful, and unaware– you can almost hear her quiet naive breathing. The winged man, still in the process of abandoning her, reaches towards his clothes and arrows with his right foot still lingering on the bed. The rich pinks, reds, and yellows combine with the beautiful Eden-like background, making the whole painting seem like a dream. The angel looks back at the sleeping beauty with a goodbye glance– the older cupid teaching us that love, if anything, is fleeting, and you never know when you’ll wake up and your arm will be outstretched around nothing.