Nov 6, 2016 | installation, public art

Hanieh Alizadeh, Mahmoud Ganji, Mehdi Rabie (EOT design studio). Whispering Rainbow, 2012. Satin ribbon. Hefdah-E-Shahrivar Street, Tehran. Photo via EOT design studio’s Facebook.

When every object we touch is factory-made, are manufactured environments somehow more real? Both Alexandra Kehayoglou’s Shelter for a Memory and EOT design studio’s Whispering Rainbow are knowingly synthetic; they mimic the earth’s beauty as a tribute by celebrating some of the most joyful natural elements. Shelter for a Memory’s delight arises from a collaboration between man and nature — a wooden swing that within the myth of the scene hangs from a towering, enveloping tree. In a similar way, Whispering Rainbow is a collaboration through appropriation, a reenvisioning of a rainbow remade in 150 rolls of satin ribbon (a potentially natural medium). When the wind blew the satin shook to create the sound of rain, adding an audible dimension to the rainbow’s recreation.

Whispering Rainbow evokes only happiness, and its installation across a public street in Tehran makes seeing it fun and serendipitous. Shelter for a Memory differs in both respects: viewers enter its space with certain expectations because of its place in a gallery, and the scene’s deliberate edges create a conceptual frame that conveys a sense of disillusionment and inauthenticity when seen from a distance. But its title acknowledges the potential for fiction in nostalgia, and Kehayoglou creates her wool rugs through a hand-tufting process that lends a truth to the piece. Together, both installations ask: can an artificial environment carefully crafted by human hands be more real than the nature it imitates?

Alexandra Kehayoglou. Shelter for a Memory, 2012. Wool, paint, wood, rope. Photo: Artist’s website.

Hanieh Alizadeh, Mahmoud Ganji, Mehdi Rabie (EOT design studio). Whispering Rainbow, 2012. Satin ribbon. Hefdah-E-Shahrivar Street, Tehran. Photo: EOT design studio’s Facebook.

This text was originally written for a class titled Installation Art: Design & Change at Pratt.

You can also read more pairings on the Pairings: Blog set up by our professor, Kim Connerton, PhD.

GD Star Rating

loading...

Mar 6, 2013 | sculpture

“Throne For The Greatest Rapper Of All Time,” 2005

Found Wood Furniture, 96”h 69”w 48”d

Marc Andre Robinson creates sculptures, drawings and videos from his studio in Brooklyn, all of his work concerned with family and what it takes to belong in one.

His works with chairs show a playful relationship between art and artifact, using found furniture that has probably held the generations of many families within them, giving each piece a stronger sense of realness – art repurposed instead of just created for its own sake.

“Throne For The Greatest Rapper of All Time” looks like either a very elaborate 19th century sex toy, or a complete dining room set come to life, becoming a more powerful Transformer-version of chairs and pieces of table. But the work is very sit-able, and looking closely you’ll see all the stacked chairs come from different sets and different tables. Wooden antennae stretch up symmetrically creating a very impressive silhouette, the backs of the chairs exaggerated and elongated, like a father figure overcompensating.

“By Themselves And Of Themselves” accomplishes a feat against gravity, a huge circle of interlocking chairs standing upright. All the chairs face out, some are plastic but most are wooden, and again each chair comes from a different set – a mismatched bunch somehow made whole.

See more from Marc Andre Robinson on his website.

“Throne For The Greatest Rapper Of All Time” (detail) 2005

Found Wood Furniture 96”h 69”

“By Themselves And Of Themselves,” 2008

Found Wood 192”h 192”w

GD Star Rating

loading...

Nov 16, 2016 | interviews, painting

Judith Seligson

Signs Of Struggle, 2016

Oil on panels

8.5 x 8.5 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Colors fracture, shapes surface, and together the two work in tandem to continue Josef Albers’ exploration of minimalist, geometric compositions. Judith Seligson’s new exhibition Drawing the Line is comprised of elegant, cheerful examples of shape and color getting well acquainted.

How did you begin in geometric painting? What was the initial spark of inspiration for you?

I developed a series of charcoal drawings in my first studio, in Cambridge, MA in 1973, just after I graduated from Harvard, that presaged everything that was to come. I was drawing from life; both the studio itself and a vase of my mother’s dead roses were my subjects. Despite charcoal’s propensity for infinite shades of gray, I found myself using the charcoal simply to outline discrete empty shapes. Each petal surface was a shape. This method flattened objects and made them of a piece with everything else in the work, like tesserae in a mosaic.

At that time, too, I was studying a book called Cézanne’s Composition: Analysis of His Form with Diagrams and Photographs of His Motifs by Erle Loran. He “reduced” a painting to a series of lines of force. I began applying this method to some of my favorite Vermeers. Vermeer too focused my attention on drawing architecture.

My love of building blocks and of finding hidden structures in a painting and in life continued to grow and develop. Still, I pushed against it then and still do. In 1978 I had a show of painting pairs – each pair used the same palette, but one was geometric and one expressionist. I ended up pursuing the geometric direction, thinking that I could always pull the expressionist one off the back burner if I needed a change. When I look at those small painting pairs now, I find the expressionist ones much better than the geometric ones.

Judith Seligson

Golden, 2016

Oil on panel

7 x 7 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Galérie Mourlot describes your work as having a “feminist bent.” In what ways do you see your work as uniquely feminist?

Here is a quote from my article, Contrapuntal Painting, which appeared in the Radcliffe Quarterly, March 1992:

“Many of my paintings are diminutive, intimate, three to five inches in either direction. Rather than physically overpowering (as many men are to women), they suggest a more interactive relationship with the viewer. Smallness in art may be coming under a more favorable star, but in my lifetime size has mostly been a directly proportional measure of importance and, though no one would admit it, quality. The small works are painted on paper. Arthur Danto has aptly pointed out that paper, since it is so expendable, is considered a less “serious” medium than canvas, panels, or walls, and so has become associated with the artist’s “intimate moods.”

“Paper and women have a lot in common in that they both have developed a reputation for being less than serious but good for intimate moods, and maybe even expendable. I take these stereotypes, these preconceptions, and play with them. I draw on the bare paper — actually four-ply museum board — and then apply multiple layers of a gesso wash to protect the painting from the board. This way I can be serious, intimate, expendable, and conservable all at once.”

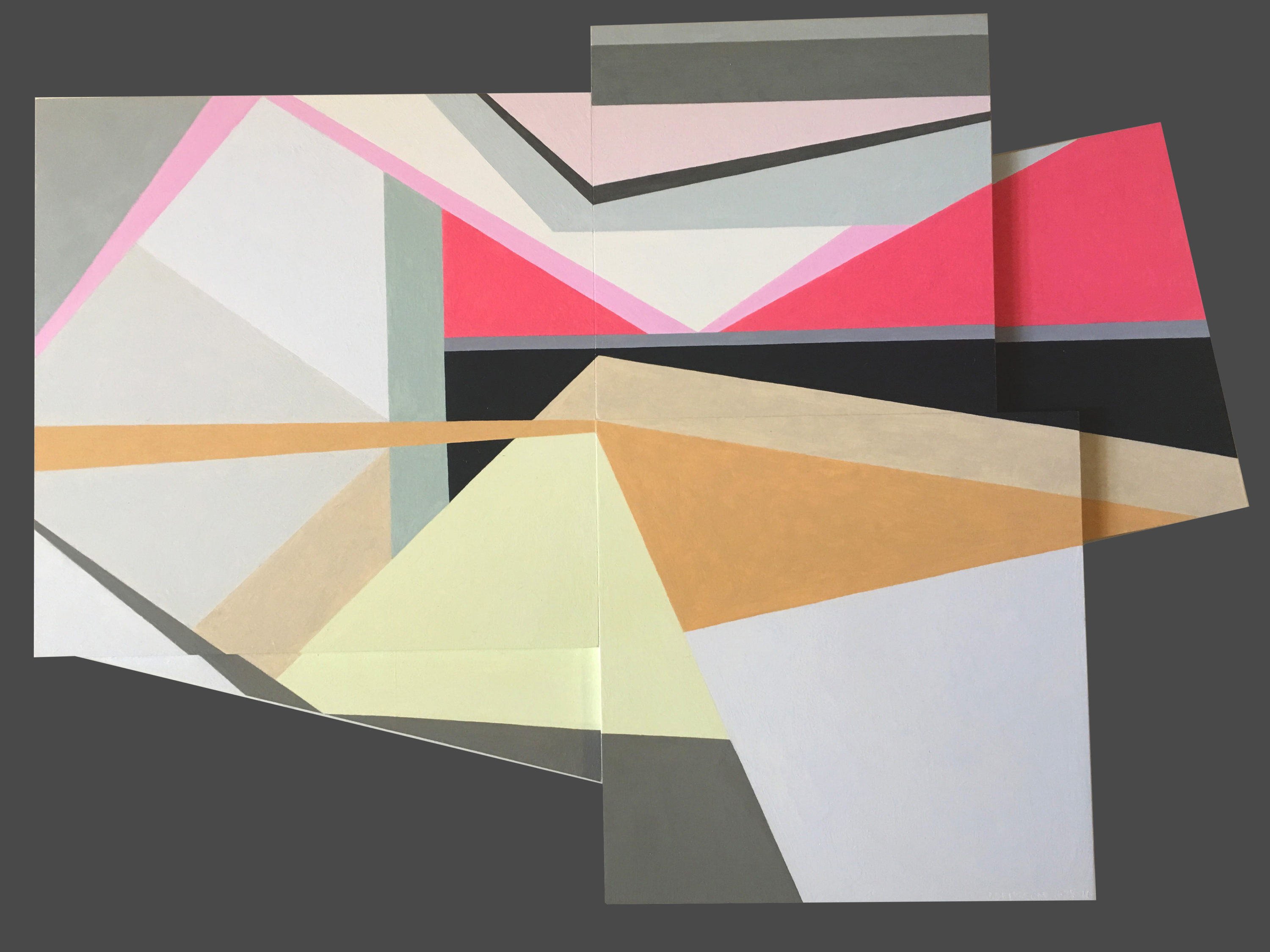

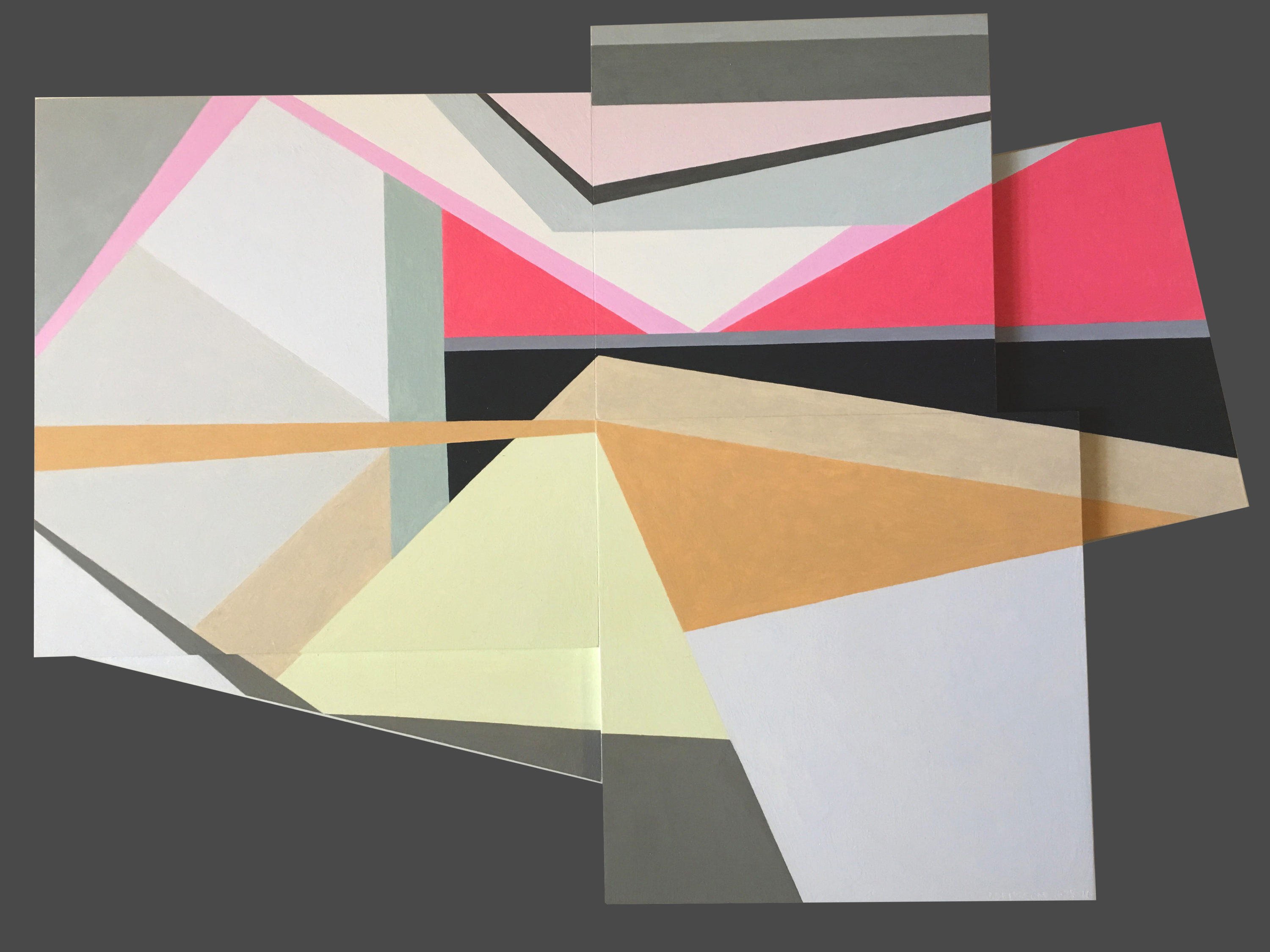

Judith Seligson

Healing Brush, 2016

Oil on panel

6 x 6 in.

Courtesy of the artist

When did you first introduce three-dimensionality to your work?

About four years ago. I was making a series of collages using, among other things, fragments of my own paintings. These were works I didn’t love or didn’t think were finished, but couldn’t toss. Then I started placing paintings that I had signed into a single composition. That led to adjusting one or the other to improve the composition. Then I started gluing together completely blank panels. At that point, I didn’t know how I wanted to paint them. I looked at them for over two years until I figured out the topological painting in Fine Tuned.

Judith Seligson

Complications, 2016

Oil on panel

11 x 16 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Can you walk us through the process of creating one of your works? Which comes first, color or shape?

The chicken or the egg. Each painting begins with a graphite line drawing. Usually, I draw directly on the painting surface. Sometimes, I trace a drawing onto a panel, or enlarge a small drawing onto a larger surface. I draw and erase until I see the blank shapes pushing and pulling, à la Hans Hoffman, moving in the shallow 3-D illusionary space created by an interplay of color and form.

I then apply several layers of thinned gesso, sanding between layers, to get a very smooth surface. The drawing is still visible, but the graphite will not mix with the paint.

Positive shapes, like a vase, will appear in front of a negative shape, like the shape around the vase. Matisse said that painting begins when you can see both the vase and the space around it at the same time. Warm reds push forward, blues recede. I work each against the other so that the color shapes are pushing and pulling my eye around the surface in what I call I visual melody. I will use a cool color to push back a shape that appears too forward, or a warmer color to pull forward a shape that is receding. Like a great song, a visual melody is a whole structured by notes, tempo, dynamics, and a sense of beauty – or is it pleasure? Each shape is a note in several simultaneous visual melodies, playing on the scales of hue, tone, temperature, intensity, and negative/positive shape. I have called my work Contrapuntal Painting, in that counterpoint in music is created by two or more melodies played simultaneously. Each is both an independent melody and also the harmony to the other.

In this sense, too, my work is feminist. Man and woman can be the counterpoint to each other, rather than the woman traditionally being only the harmony to the man’s melody.

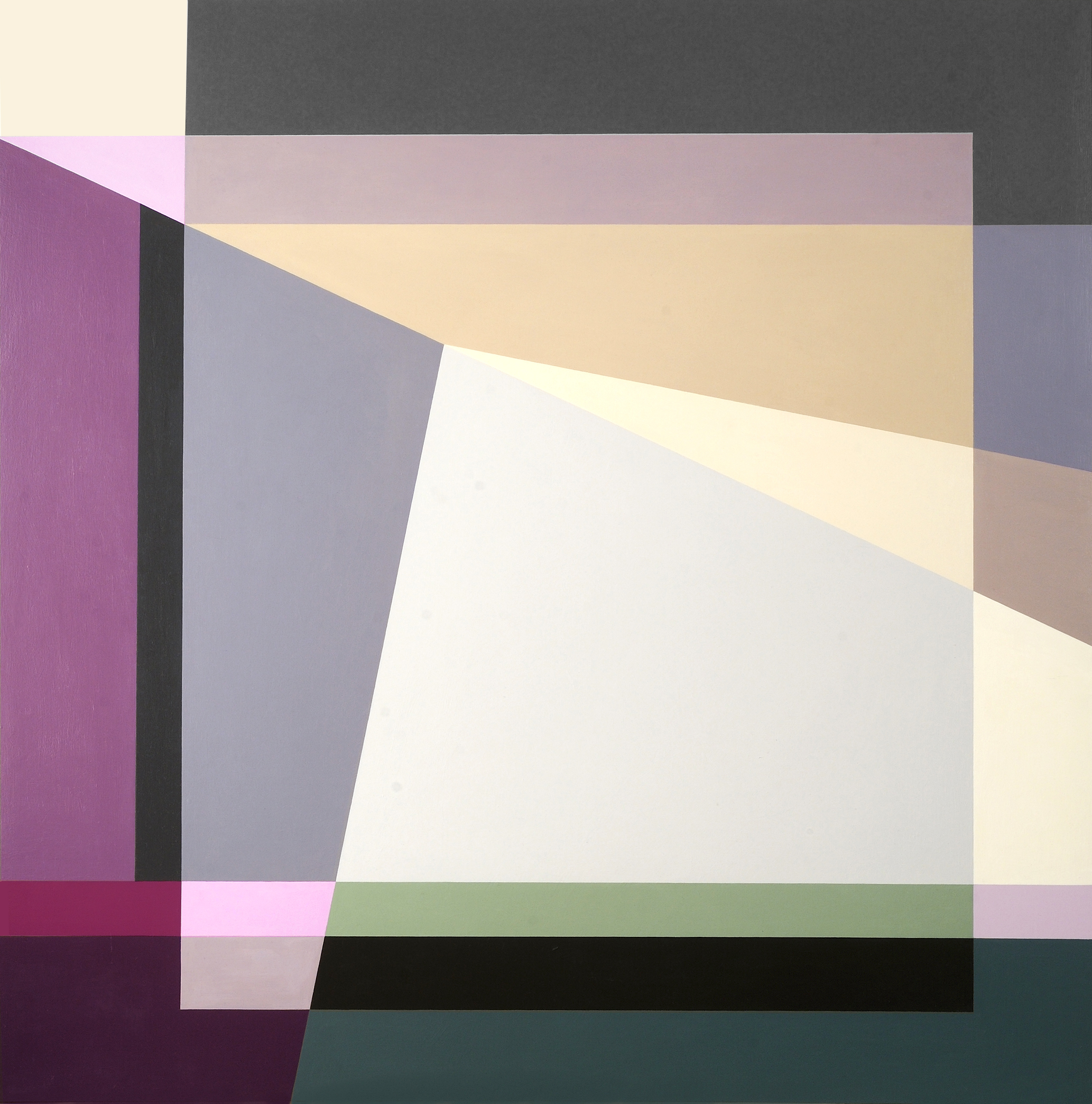

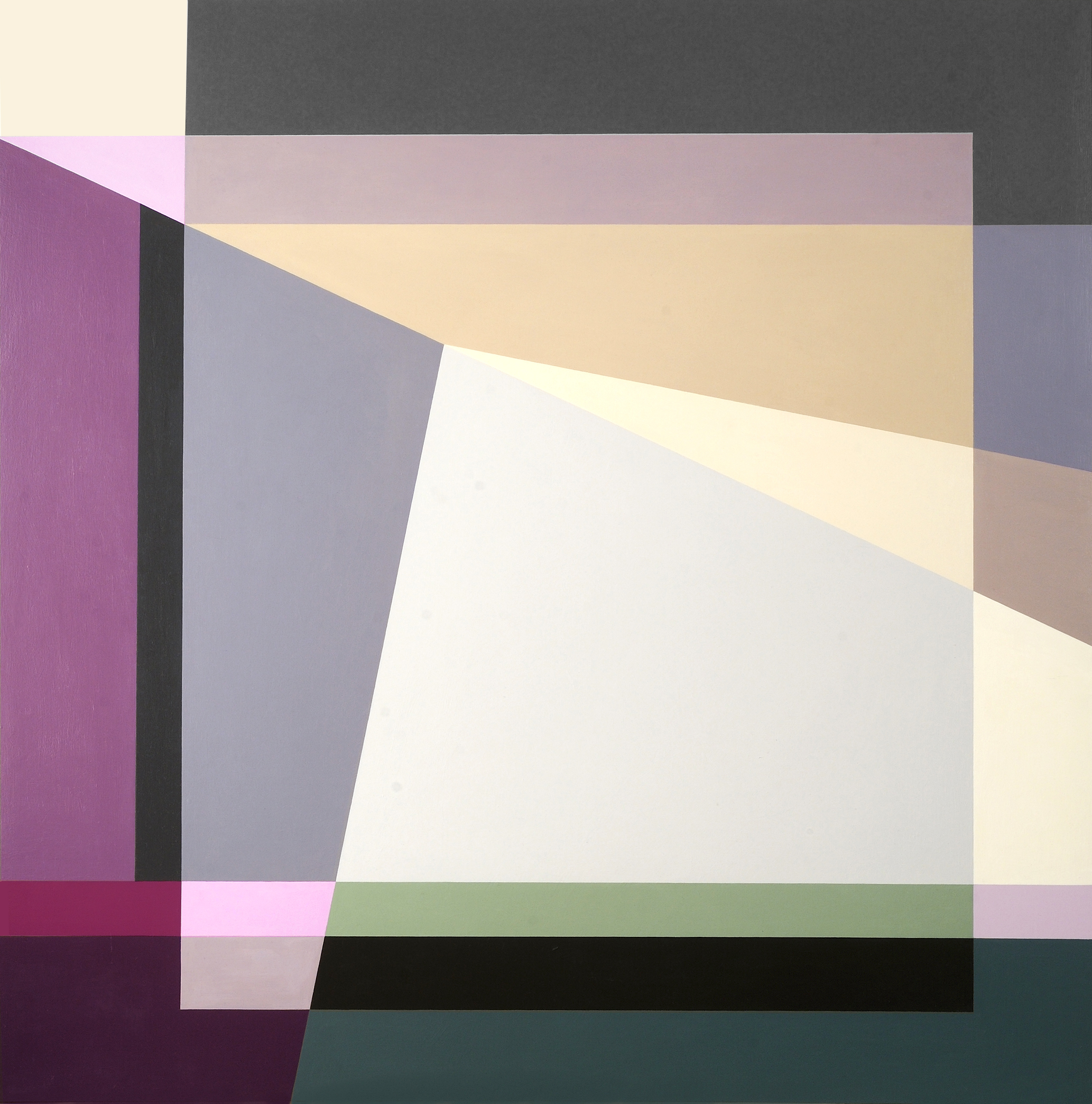

Judith Seligson

Self Portrait, 2014

Oil on panel

36 x 36 x 2 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Which artists or websites do you most often find yourself looking towards for inspiration?

I look to many of the Dutch painters – Rembrandt, Vermeer, Mondrian, and de Kooning. Their devotion to structure and to light in a painting is a constant inspiration.

I like Elizabeth Peyton’s small portraits and Cecily Brown’s paint handling. I like Peter Halley’s electrical circuit paintings. I look at and read Artforum and Bookforum in print. Intermittently, I read artnet News, Hyperallergic, and Blouin Artinfo.

Judith Seligson

Candy, 2008

Unique digital painting on canvas

43 x 43 in.

Courtesy of the artist

Drawing the Line opens tomorrow, November 17 at Galerie Mourlot on 79th Street in Manhattan where it will remain on view through January 9, 2017.

GD Star Rating

loading...