Jun 26, 2012 | Museum of Fine Arts: Boston, sculpture

|

| Bronze |

An abstract human form sits at an angle on a curved bench. There’s no focus at all on accuracy or perfection here, which somehow just makes it more pure. Moore wasn’t worried about the head-to-body ratio or even choosing a sex for this figure– he seems focused on the positioning of the long legs and arms, and the framing of the figure against the curved backdrop.

The entire piece is a rough brown monochrome that seems to exist somewhere between wood and metal. The bronze is easily masqueraded as wood in the curved wall, with horizontal lines that resemble a tree more than incised metal. The figure has shoulders that reach too far back and a head that seems to jut out of its torso, but above the head the wooden wall rises, framing the figure asymmetrically as he or she looks and gestures across the space.

May 29, 2012 | Museum of Fine Arts: Boston, sculpture

The figure of a young girl crouches above you on the wall like Spiderman. Her bronze body is splotchy and rough, especially in her hair that’s pulled back into a kind of ponytail. It’s interesting enough until you walk around her and stare her straight in the face– or eyeballs actually. Very realistic-looking glass eyeballs in a light brown color stare right back at you. It’s unnerving really.

Feb 28, 2012 | installation, sculpture, The Whitney Museum

|

|

Lion and Cage from Calder’s Circus, 1926-31, from thecityreview.com |

Wire and fancy. That’s how I would describe this piece, or pieces rather. Three huge sets of miniature circus performers made of made of metal, wire, fabric, and yarn. A metal plated kangaroo the size of my hand rolls on ribbed washers. A clown wearing multi-colored layers topped by a lion coat has an almost ironically painted smile of red on his small wooden face. A lion with a plush face, yarn mane, and wire body is being tamed outside his cage by his wire-bodied master. And there’s tight-rope walkers, cowboys, acrobats, sword swallowers, everything expected of a circus setting, even the ringnmaster. I think I like it so much because there’s something about the idea of the circus that lends itself to being portrayed through this fanciful, although unglamorous, medium of wire.

|

| Calder’s Circus, 1926-31, from the Whitney Museum of Art’s website. |

|

| Alexander Calder, Roaring with his Circus Lion, 1971, from kaufmann-mercantile.com . |

Nov 22, 2011 | sculpture, The Met

I’m just going to be honest, in this statue she looks like a dude. From the neck up, she could be a man– her face is really masculine and you can’t see any of her hair because it’s all covered up by her khat (or, pharoah hat). If her dress hadn’t slid down quite scantily to reveal her entire left breast, she could have easily been mistaken for a boy.

She is wearing a very crisply carved flowing dress that hangs around her stone body as if it were actual fabric. Her doubled beaded necklace has a huge centerpiece hanging from it that looks like it would have been pretty heavy in real life. But for all this glamour she looks upset, her eyebrows are furrowed and her right arm is propping up her head and casting her gaze downward, like the answer to whatever problem she’s having is somewhere on the floor. Or maybe she’s just upset that she’s been put by the wall where no one can see her, instead of out in the middle of the gallery exhibit where all the more naked, more feminine statues stand.

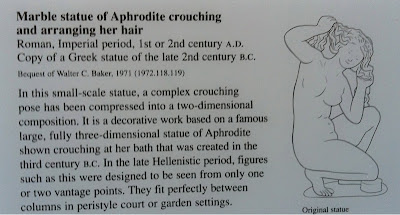

Sep 1, 2011 | sculpture, The Met

The curvature of her back leads your eyes to where the rest of her body might have been. She’s missing her bent left leg, her head and both arms, but the crouching position the remaining parts of her body are in could leave this miniature woman doing pretty much anything. Her shoulders are twisted as if she’s falling or leaning, and the accuracy of her back and torso muscles beneath the layer of stone skin makes this sculpture beautiful despite what it’s lost. Even without seeing the front of this headless sculpture, it’s clear that it’s a woman even at first glance- her full hips and dainty shoulders give her away immediately.

Even though the museum’s supplied a pretty crude representation of what this statue might have looked like, what’s left is still a million times more beautiful.

Jul 14, 2011 | sculpture, The Met

She looks so effortlessly sexy. Her arms lifted over her head and her eyes looking down. She just looks real. She has small breasts and wide hips, and even though that seems so different form what’s considered “sexy” in this plastic-surgery/spray tan/skinny minny society we live in now, this woman and this statue makes it very obvious that sexiness in its purest form comes from the way you carry yourself and not the body you were born in. Because bodies are things, just an exterior. And the way you hold yourself shows how you feel about who you are instead of this sad Real Housewives “ideal” we see so many women striving for. But this statue and this woman don’t have to try, and she doesn’t even look posed—just captured in time as no one else but her.