Saul Steinberg’s Wonderful Places

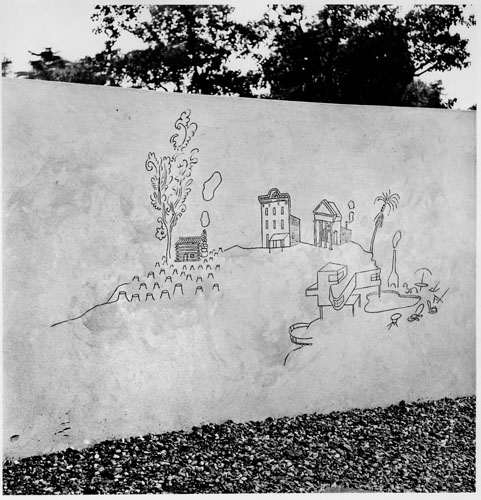

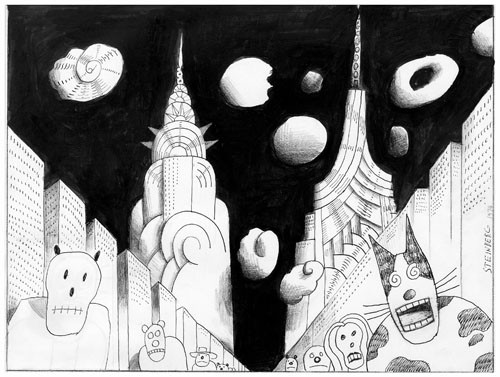

Children’s Labyrinth, 1954.

10th Milan Triennial, detail of History of Architecture section of mural.

Saul Steinberg‘s illustrations combine whimsy with art, creating mini-worlds that are clean and simple but at the same time lead the eye to someplace happy and bright.

Like a refined dose of Dr. Seuss, Steinberg prefers to draw realistically, turning typical scenes into magical places where the trees stretch up taller than the buildings – a small detail that makes our world seem more like a simply designed amusement park where thrill and wonder fill the air.

His work for the New Yorker explains all the scenes of the city, but I prefer the imaginary “Children’s Labyrinth,” drawn as part of the History of Architecture section of a mural. On the left sits a log cabin surrounded by the stumps of the trees those logs used to be. The most beautifully detailed tree stands next to the little building puffing smoke; the tree’s branches take delicate curlicue shapes as they expand just like the smoke beside them.

See more of Saul Steinberg’s work online at the Saul Steinberg Foundation Gallery.

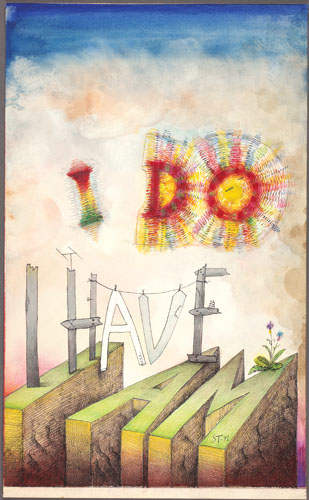

I Do, I Have, I Am, 1971.

Ink, marker pens, ballpoint pen, crayon, gouache, watercolor, and collage on paper, 22 3/4 x 14″.

Cover drawing for The New Yorker, July 31, 1971.

The Saul Steinberg Foundation.

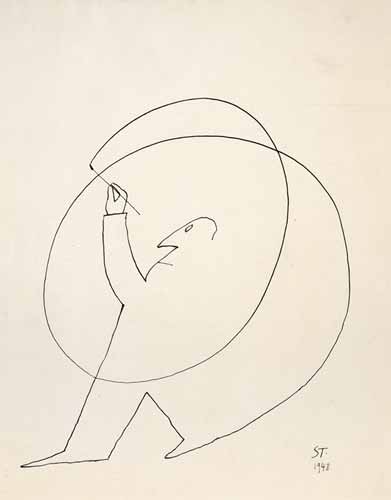

Untitled, 1948.

Ink on paper, 14 1/4 x 11 1/4″.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

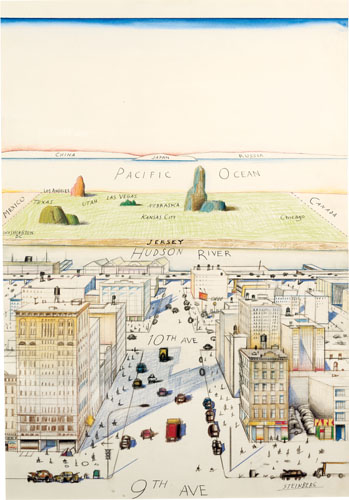

View of the World from 9th Avenue, 1976.

Ink, pencil, colored pencil, and watercolor on paper, 28 x 19″.

Cover drawing for The New Yorker, March 29, 1976.

Private collection.

Untitled, 1974.

Ink, colored pencil, and collage on paper, 14 1/2 x 19 1/4″.

Originally published in The New Yorker, July 22, 1974.

The Saul Steinberg Foundation.