May 16, 2013 | art history, Art Institute in Chicago, painting

A painter paints another painter in this picture, a man in blue holding a palette of colors. And since this is Picasso, it’s done in a style based off of his own. His figure is disjointed and geometricized, turned into shining cubes of color that hold pieces of a nose here and an ear there. It’s like looking at a realistic work by Picasso through an organized kaleidoscope.

Juan Gris was a Spanish painter and sculptor who met Picasso in France after moving to Paris in 1906. Gris regarded Picasso as a teacher, but Gertrude Stein wrote “Juan Gris was the only person whom Picasso wished away.”

These photographs were taken at the Art Institute in Chicago.

For more pictures of this museum’s work, see my Flickr album.

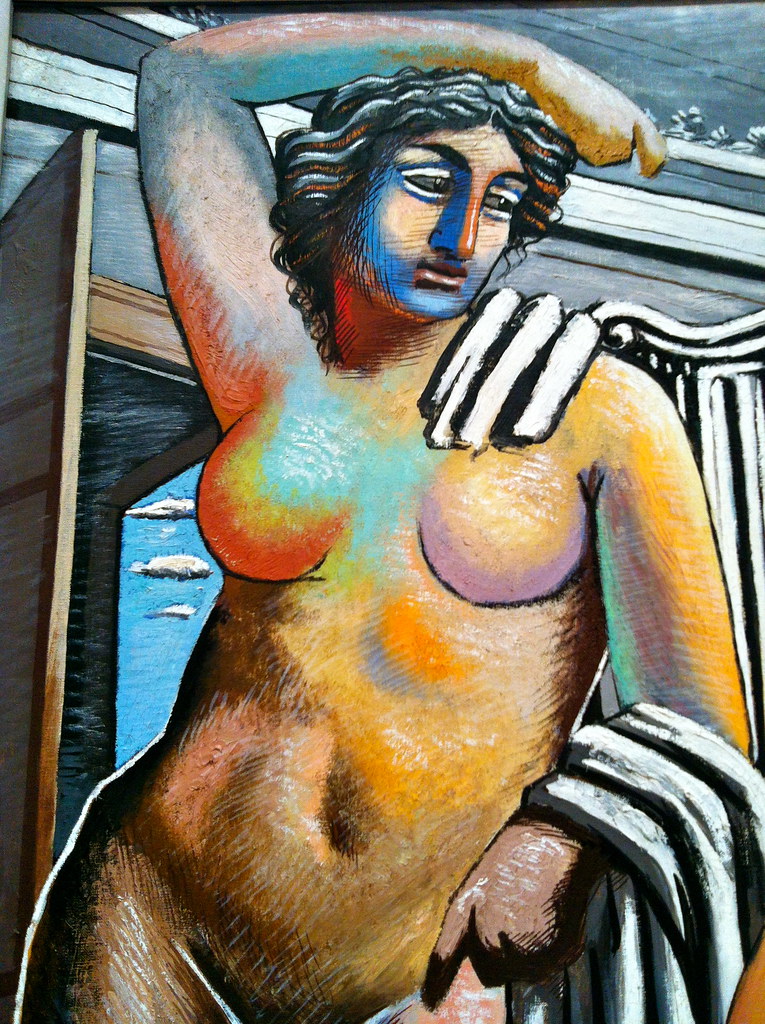

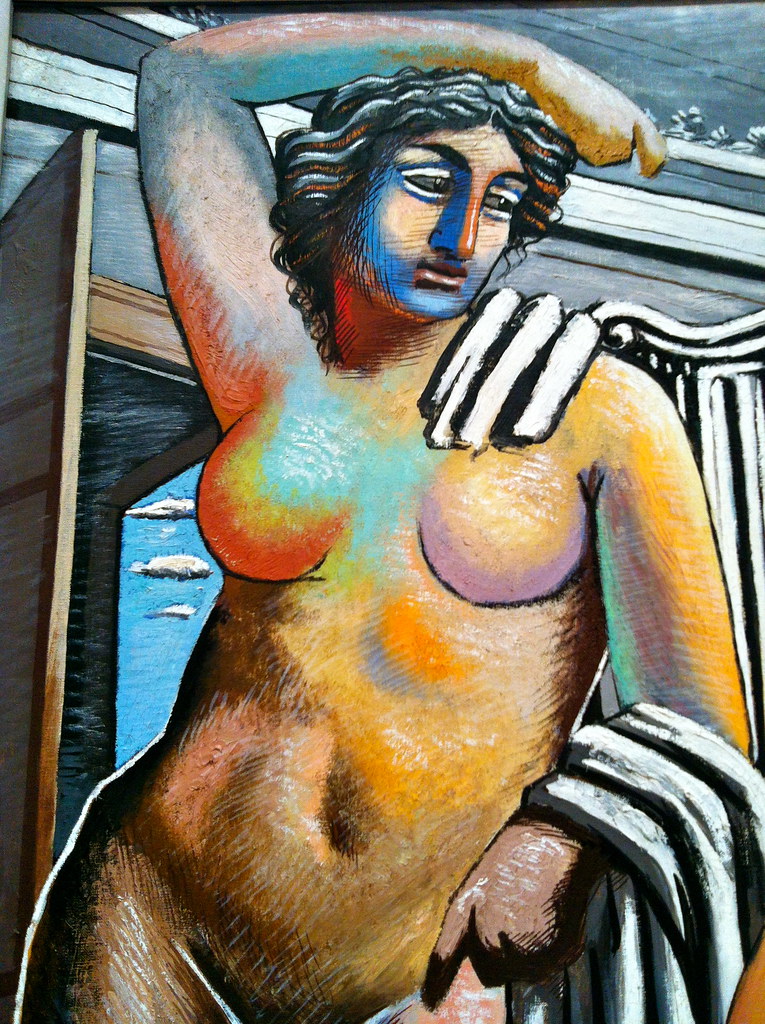

Apr 25, 2013 | art history, Art Institute in Chicago, painting

“The Eventuality of Destiny” shows what could be the Three Graces, or just three random goddesses who are trapped on all sides by gray walls and ceiling. The architecture creates a sense of confinement that’s relieved only under the arm of the featured goddess – a little patch of blue sky that holds three tiny clouds.

This featured goddess stands tall with her arm gracefully draped over her head, and her whole body seems to glow from within with bright fiery colors. The greens, blues and oranges nearly burst out of her assumed human form, and the only sitting goddess looks like she holds whole universes within her. The women overtake the manmade architecture behind them, three maidens in elegant postures and only one reveals her face, bright blue shadows cast across her cheek with the tops and bottoms of her eyes lined in bold streaks of white.

An Italian artist born in Greece, Giorgio de Chirico imagines the Greek goddesses as colossal creatures, perfect in form and covered in color. This painting gives a glorious hopeful portrayal of the supernatural beings in charge of our universe, and yet they’re still confined within the boundaries we created for them.

[zl_mate_code name=”twitter/facebook” label=”5″ count=”2″ link1=”http://www.twitter.com/share?url=https://thingsworthdescribing.com/2013/04/25/the-eventuality-of-destiny-by-giorgio-de-chirico-1927/” link2=”http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://thingsworthdescribing.com/2013/04/25/the-eventuality-of-destiny-by-giorgio-de-chirico-1927/”] [/zl_mate_code]

[/zl_mate_code]

Photographs taken at the Art Institute in Chicago. For more photos from this museum, see my Flickr set.

And for more information about this painting or de Chirico, check out this JAMA article.

Apr 24, 2013 | art history, interviews

Ben Street is a freelance art historian, writer and curator based in London. He has lectured for the National Gallery for many years and also lectures for Tate, Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Saatchi Gallery and Christie’s Education. Ben writes for the magazine Art Review and has published numerous texts for museums and galleries in Europe and America. He is the co-director of the art fair Sluice, and has curated a number of contemporary art shows at galleries in London. More information can be found at www.benstreet.co.uk.

Ben kindly answered some questions about how he got to where he is, and what it’s like to share art professionally in pretty much every way possible. He works with art that spans centuries, lecturing in the halls of prestigious museums while curating and covering contemporary art for modern magazines and galleries.

How did you come to realize that studying fine art was what you wanted to do with your life? What is it about art that makes it worth your dedication?

I got into art by making art, which I don’t do any more (at the moment, at least, to the great relief of many of my artist friends). Through painting, I became interested in various painters (Bacon, Grosz, Beckmann, people like that – I was a teenager, obviously). I remember seeing retrospectives in London of Picasso and Pollock, and the New York Guggenheim’s big Rauschenberg retrospective, which sparked a fascination with twentieth-century art, and I came to older art much later. (Initially I found it – older art, of the Renaissance and so on – incredibly difficult to grasp, which is the opposite way around to how it usually works). I can’t quite work out what makes art worth all this time, but I can’t stop spending all my time on it. I never feel like I know enough, that’s the motivation. Even paintings I’ve seen literally hundreds of times, and have written about and researched extensively – I feel I barely know them, which is an exciting feeling.

Can you remember the first work of art that had a really deep, profound impression on you?

I don’t think early experiences of art are really about deep and profound impressions. They’re about a gradual and insidious seeping into the subconscious and slow possession of the psyche, like an anaconda slowly suffocating a missionary explorer, and once you realise it’s happened, it’s too late – you can’t wriggle out again. I didn’t see that much famous art until I was a teenager, and even then it was mostly in books or on postcards. Consequently I have probably a deeper relationship with reproductions than with ‘real’ works of art – I have a sneaking suspicion they can be just as good as the original thing.

How does your knowledge and experience in lecturing play a role in the curation process for new work?

I have no idea – in fact, I’d try and avoid any crossover there for fear of being didactic. The worst curatorial policy begins with a theme and seeks works of art to illustrate it. Although I’d like my teaching/lecturing to be more about facilitating conversations between works of art across history, which is my idea of interesting curation, rather than regurgitating all the facts I’ve read, which is my idea of bad teaching.

Would you consider yourself an “art critic” at all? What does an artwork need to lack or have for you to absolutely hate or love it?

Yes, because I review exhibitions for Art Review magazine. Every really good work of art sets its own criteria by which it should be judged. There isn’t a universal measure, in other words. This is true of Titian as much as it is of Donald Judd, Matisse, David Hammons, or Duccio, to name a few artists I’ve been pretty obsessed with recently. It’s about a certain kind of force which obliges you to reassess what you thought you thought. That force is not dependent upon scale, or historical period, or medium. You know it when you see it – like pornography.

Whether lecturing or writing, how do you gauge the appropriate style that will reach the audience most effectively? Do you base it on their level of knowledge, assumed interests or something else?

I’d like very much to communicate ideas in a clear and comprehensible way, without compromising the complexity of those ideas. Sometimes that works and sometimes not. I’m very much in favour of encouraging people to look closely at works of art, and to be prepared to work hard (thinking, looking, analysing, discussing) to reap the big rewards. Looking has to be active and thoughtful and switched-on, but our world conspires against that: we see more images than ever, but our seeing has become passive – images require giving, not just receiving. Works of art are like gyms for the eyes, and once you start working out – stay with me – your life will be enlivened in a quite amazing way.

For more from Ben Street follow him on Facebook and on Twitter.

Dec 3, 2012 | art history, museums, painting, The Met

In 1906 Henri Matisse painted “Young Sailor I,” a roughly shaded, almost abstract interpretation of an eighteen-year-old fisherman in his neighborhood. The young man is shown sitting with his arm propping up his head, his features outlined in dark black lines, and the same green of his pants creeping up to his cheek indicating shadow. Matisse lived with this portrait he’d created for almost a year before it inspired a reinterpretation that became “Young Sailor II,” one of his most iconic works. It’s clearly the same man, his hands arranged identically and his posture only slightly improved, but his face is completely different, almost unrecognizable – his eyes elongated and spread apart and his cheek bones accentuated; all traces of green-shadowed abstraction gone. Now the sailor sits in front of a glowing pink background instead one shaded in rough random lines of orange, blue, and green. Although “Young Sailor II” is now the more well-known of the two, at first Matisse was so insecure about this reinterpretation that he originally told people it was painted by the postman.

|

| “Young Sailor I” |

|

| “Young Sailor II” |

Both of these paintings sit side by side in Matisse: In Search of True Painting, the new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art opening on Tuesday, December 4th. It presents the artist as a perfectionist, constantly reworking the same compositions to see if they could be improved upon, by using a different set colors or tweaking the arrangement. It showcases the repetitive nature he was prone to as an artist, displaying some of his most famous paintings like “Young Sailor II” alongside the lesser-known masterpieces that were created first for inspiration, allowing you to compare them directly and trace his thought process from one interpretation to the next.

Read the rest of my review HERE on Woman Around Town.

And check out more photos from the gallery in my Flickr set here.

Nov 26, 2012 | art history, features, sculpture

The legend of Michelangelo was still a powerful force in the art world in Rome a century after his death, especially for aspiring artists who wanted to become legends themselves. Michelangelo’s remarkable talent in the arts, and the works he left behind to prove it afforded him the luxury of a listening audience – he was able to control how the world remembered him by instructing a faithful student to write a biography that would be seen as the most first-person account possible, especially after the artist’s death. Thirty-four years later Gian Lorenzo Bernini was born, another multi-talented artist whose primary skill was in sculpting, and he followed Michelangelo’s example, creating his own legend by closely instructing his biographer on what to write and how to write it. While Michelangelo wrote to contest false rumors purported in his first biography published by the Italian artist and author Giorgio Vasari, Bernini was sure to preemptively create his own legend before the same thing could happen to him, already having learned from Michelangelo that the artist’s own words are the most powerful way to combat any sort of negative light that could be shed upon his memory.

|

Self-portrait of Michelangelo

via Casa Buonarroti, Florence |

|

Self-portrait of Bernini

found here. |

Scholars have examined these biographies for centuries, working to prove which aspects of each were likely exaggerated or even made up altogether. Both artists had secondary biographers as well; men who knew the artists personally but wrote without his direct instruction. What is most interesting, however, is Bernini’s adaptation of the biographical formula set forth by Michelangelo in his own instruction to Domenico, especially concerning Ascanio Condivi’s The Life of Michelangelo. He probably did not have a copy of the text in hand while instructing his son, and there was a biographical standard for artists thanks to Vasari’s Lives, but even so the similarities between the Condivi and Domenico’s biographies cannot be ignored. Bernini was sure to stress some of the same artistic attributes, but also added information or anecdotes that he probably considered to be improvements, almost as if he were still competing with Michelangelo in the very final art of the legend-creation. These lessons Bernini took from Michelangelo could even be broadened to include how he conducted himself throughout his career, carefully avoiding Michelangelo’s mistakes with the papacy and instead branding himself an artistic genius that was also easy to work with. The first time Bernini was granted the presence of a reigning pope, Paul V said, “This child will be the Michelangelo of his age;” a comparison Bernini surely kept in mind as he went to record how he wanted the world to remember him.

Condivi and Domenico had very different approaches in the way they wrote these biographies, which may be one of the first indications that Bernini was working to make his legend seem even better and more credible than Michelangelo’s. Condivi writes The Life of Michelangelo completely in the first-person, always acknowledging that the book is merely his recordings of what happened, admitting that he is not a writer but instead an “honest collector” of truth. He begins with a letter addressed to the “Holy Father,” followed by another addressed “To the reader,” and in both he makes very clear that his intention with this biography is to honor his master and set the record straight because so many “have said things about him which never were so,” including most notably the first edition of Vasari’s biography which was later revised upon the release of Condivi’s. Domenico’s biography on the other hand is written entirely in the third-person, and he refers to himself only as the “author of the present work,” even where he talks about “Domenico” being the last of Bernini’s sons. By phrasing things as an outsider when in fact he was just the opposite, Domenico makes the stories appear more factual because they are presumably being presented by a third party and therefore with less bias. Bernini is attempting to reveal his life as a straightforward account of events that could be told by anyone; perhaps he felt that Condivi’s first-person narrative sounded too much like a fan letter, and by keeping the author and story separate in his own biography, it would appear as a more serious transcription of reality.

Michelangelo and Bernini had very different relationships with their fathers, part of the story that Bernini used to his advantage, as a way of suggesting that destiny was paving the way for him like it had not for Michelangelo. Of Michelangelo’s father Condivi writes, “On this account he was resented and quite often beaten unreasonably by his father and his father’s brothers who, being impervious to the excellence and nobility of art, detested it and felt that its appearance in their family was a disgrace.” On the opposite side of the parental spectrum, Domenico writes that Bernini’s father “gave his son the freedom to work as he wished, since he realized what higher aspirations were at work motivating the youth to make such great progress.” While Michelangelo’s story of struggle against his father might resonate more with a modern audience who have come to associate artists with some sort of strife, Domenico crafts Bernini’s fortune into fate, writing that “Heaven” had destined Bernini for greatness, laying the foundation with a supportive father so that the artist would have every opportunity to succeed. This theme of divine intervention on Bernini’s behalf continues throughout the entire biography: “But, in fact, we can justly conclude that the circumstances had been orchestrated by Heavenly Providence Most High, which, from that moment on, desired to prepare the hearts of future popes to be favorably disposed toward Gian Lorenzo.”

Success in seventeenth century Rome meant being in the favor of the reigning pope, which is why this intervention by Fortune and Heaven on Bernini’s behalf is almost always connected to the papacy. Bernini’s love affair with the papal throne is by far the biggest difference between he and Michelangelo, both in their lives and biographies. Domenico always includes mention of the death of each pope along with a description of the selection process for the next one, usually to draw attention to the fact that the next papal successor already loved Bernini, especially in the case of Urban VIII. The same day Urban was elected he called Bernini to his office and said, “It is a great fortune for you, O Cavaliere, to see Cardinal Maffeo Barberini made pope, but our fortune is even greater to have Cavalier Bernini alive during our pontificate.” Indeed Bernini’s every action is made with the pope in mind, a lesson he seems to have learned from Michelangelo who left Rome when the pope offended him, and sacrificed more than fifteen years worth of commissions after losing the favor of Pope Leo. Michelangelo was notoriously difficult to work with, a stubbornness that came through in Condivi’s writing; when Pope Julius kept asking when Michelangelo would finish the Sistine Ceiling, he repeatedly answered, “When I can.” Bernini created the opposite reputation for himself, always appeasing, obliging and “kissing the papal feet,” almost becoming an entertainer, and indeed Domenico even grants a whole chapter to Bernini’s work in writing and directing Comedies. Bernini’s reliance on the pope for his extraordinary success is reflected in his biography, a large chunk of which is dedicated to discussing the papacy.

|

Michelangelo’s David

found here. |

For Michelangelo’s David, Condivi begins with how the piece of marble was quarried in a shape that limited the figure so much that no one had been able to make any use of it, writing that once Michelangelo was done he was able to form the shape so perfectly to the original block of marble that the rough parts could still be seen on the top and bottom. He continues on to say that this ability “is characteristic of great artists and the mastery of their art,” then praising it even further and concluding with how much money it earned. Of Bernini’s David Domenico is exceptionally brief, only telling of how Cardinal Maffeo Barberini frequently held the mirror “with his own hands” so that Bernini was able to sculpt his own features “doing so with an expressivity completely and truly marvelous.” Both biographers admire their artists but Condivi focuses on Michelangelo’s ability to create within confinements while Bernini is praised for dynamism and expressiveness, in a story that, as expected, includes the involvement of a future pope and Bernini’s biggest eventual benefactor.

Domenico’s The Life of Bernini also included a number of sections and topics that were never discussed in Michelangelo’s biography, a selection of improvements, including a rather large section dedicated to Bernini’s own religious beliefs and his strong conviction in the Catholic faith. Condivi hardly included any mention of Michelangelo’s personal beliefs, which could result in Michelangelo appearing mad rather than spiritually inspired. In one passage Condivi writes that the artist dedicated himself to his art so much that “the company of others not only failed to satisfy him but even distressed him, as if it distracted him from his meditation,” a meditation not linked to the Catholic faith. Contrarily, Domenico describes Bernini as a theologian as well as an artist; Domenico dedicates a sizable portion of the final two chapters to descriptions of Bernini’s extreme faith and piety: “So much did he become inflamed with these spiritual sentiments and so high did the acuity of his genius ascend, that the aforementioned men were astounded that someone who had not dedicated his life to letters could so often not only succeed in intimately penetrating these most sublime mysteries, but also raise probing questions about and offer logical accounts of the same…” Similarly, Domenico tells of Bernini erecting his painting of Jesus on the cross at the foot of his deathbed, and he spoke with many religious leaders in his final days. Including these mentions of Bernini’s own spiritual convictions brings even more substance to the works he spent his life creating because he actually believed in the messages they were purporting. The same may have been just as true for Michelangelo, but it is a point that he did not stress to Condivi for inclusion in his biography, which results in the impression of a slightly mad Michelangelo and a divinely possessed Bernini.

In the same way that Bernini learned from Michelangelo’s mistakes, he was also sure to learn from his successes; both biographies heavily stressed the artist’s virtues of piety, self-motivation, modesty, and generosity, both with their money and with their craft through teaching. Michelangelo’s abstemiousness is a character trait Bernini works to duplicate in his own biography; Domenico repeatedly includes mention of Bernini not eating because he was so enraptured by a project or too dedicated to his work to be bothered. Domenico writes that Bernini “was abstemious in eating,” and for the marble portrait of Cardinal Borghese, Bernini, “except to replenish his energy with a bit of food, did not rest from this labor for the space of three days, when he brought the work to completion.” These mentions seem to be derived at least subconsciously from Condivi who writes, “Michelangelo has always been very abstemious in his way of life, taking food more out of necessity than for pleasure, and especially while he had work in progress, when he would most often content himself with a piece of bread which he would eat while working.”

Michelangelo was also abstemious sexually, a piety that Bernini could not logically include given that his biography is written by his son. Although only mentioned in a notation written down by Michelangelo’s student Tiberio Calcagni that was incorporated into later versions of Condivi’s biography, Michelangelo gave advice to “refrain from sexual intercourse in the interest of long life.” However, Bernini was sure not to be outdone by Michelangelo, and since he could not include sexual piety, he includes anecdotes that show a physical devotion to his art that is even more powerful. In his creation of the statue of St. Lawrence, Domenico writes that Bernini, “placed his own leg and bare thigh near the burning coals” in order to accurately “reflect in the saint’s face the pain of his martyrdom.” Had this inclusion been a direct rebuttal to Michelangelo’s abstinence, it would have been a very clever reversal of situation, turning a rather boring form of personal devotion into an exciting, vivid one where Bernini sticks his own arm into fire for the sake of realism in his sculpture. At the very least, it is certainly an augmentation of Michelangelo’s overwhelming desire to create works true to nature: “…he was determined to acquire not through the efforts and industry of others but from nature herself, which he set before himself as a true example.”

|

Bernini’s David

found here. |

There is another similarity between the stories told by Condivi and then Domenico that seems too close to be accidental. One of the few times Michelangelo is in favor with the pope, Julius III remarks that he would “gladly give up some of his years and some of his own blood to add to Michelangelo’s life,” continuing on to say that if he outlived the artist “he wants to have him embalmed and kept near him so that his remains will be eternal like his works.” A story from Domenico is eerily similar; he writes of a gift Bernini received from Pope Urban VIII, a magical liquid that “would revive the vital forces in marvelous fashion,” continuing, “A gift truly worthy of the affection of that pontiff, who, had it been possible, would have wanted Bernini embalmed and rendered eternal.” The use of the word “embalmed” appears to be borrowed directly from Condivi, especially considering that it was applied to Michelangelo in a direct papal quote and only inferred from a gift that Bernini received.

Regardless of how consciously Bernini instructed Domenico to write his own biography after the template left by Michelangelo, the two books do have striking parallels that at the very least confirm that Bernini had read Condivi’s work to learn the characteristics of the “artistic genius” that he wanted to apply to himself as well. Of course, Bernini’s reputation as a problem-solver prevails as he works to improve on what many considered to be Michelangelo’s faults, fulfilling what Domenico describes as Bernini’s motto: “He who does not at times depart from the rule never exceeds it.” Domenico arranges of the pieces of his father’s life in a fashion similar to Condivi’s arrangement with Michelangelo, but with more repetition of his successes and less acknowledgment of Bernini’s competition and critiques. Ironically, Domenico’s third-person biography included more overpraise and excessive flattery of the artist than Condivi’s first person account of Michelangelo. It seems as if Bernini’s attempt to leave a lasting legacy resulted in the creation of a hyper-idealized version of what he thought an artist was supposed to be; a fault that surely became more noticeable as the time passed and the biography’s readers grew smarter and more aware of how easily the truth can be shaped for personal gain.

I originally wrote this piece as a final essay for my Bernini class at NYU, hence the citations and (boring) academic nature.

Oct 22, 2012 | art history, illustration, museums, The Morgan Library & Museum

I wrote a little too much for this review, so below you can read the extra describing I did about the pieces from this phenomenal new exhibit at the Morgan.

Read the full review on Woman Around Town here.

|

| Andrea Mantegna, Dancing Muse, c. 1495 |

Last week the Morgan Library and Museum opened their first fall exhibit featuring 100 drawings by almost as many artists, all on loan from the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, or State Graphic Collection in Munich, Germany. This new exhibit was made possible by an agreement between the two institutions – in 2008 the Morgan sent 100 drawings in their collection to the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung as a part of their 250th anniversary celebration. Four years later, 100 drawings from Munich have made their way across the ocean to create Durer to de Kooning, an exhibit that fills both the East and West Morgan Stanley Galleries.

The Staaliche Graphische Sammlung has a collection of 400,000 works that began in the 1750s, growing over time until it was moved to Munich in 1794 for protection from approaching French revolutionary forces. German kings continued to add to the collection and it was opened to the public in 1823, becoming an independent museum in 1874. It was the only art institution that remained open during World War II, until July 12, 1944 when the building was bombed and almost a third of the collection was lost. But it only continued to grow in the twentieth century, adding a number of German Expressionist works and more modern and contemporary drawings, which still remains the collection’s largest and fastest growing genre.

Beginning at the High Renaissance in Italy, the artists represented are instantly recognizable, to the point where it seems as if some pieces were chosen based on name alone.

The drawing by Leonardo da Vinci seems a little out of place.

|

Matthais Grunewald,

Study of a Woman with her Head Raised in Prayer |

It looks like it came straight from an engineer’s notebook and all the pieces surrounding it are sketches of religious scenes.

Still, the names are impressive, and being able to see the actual handwriting and sketches of all these ancient artistic masters feels more intimate than standing before finished portraits and paintings. A few of the works have placards that even include an image of the finished painting, revealing the artist’s thought process as he worked out compositional arrangements and the orientation of the figures.

The first work to include the finished painting counterpart is Andrea Mantegna’s Dancing Muse. Completed around 1495, it features a young woman dressed in flowing, flying wrinkled dress with her hair parted down the middle and tied back; her arms teased behind her back as well and her body twisted and on her toes like she’s dancing in the wind. Drawn in pen and brown ink plus brown wash and heightened with white, the brown-gray paper the figure rests on is aged and near crumpling. Her ankles are fading away on the edge of the paper and her dress looks Greek and ancient, as if this could have come from thousands of years ago instead of hundreds. This ancient muse is only one character of many in the finished painting, shown in the placards as a detail of Parnassus, a tempera painting now in the Louvre.

|

Leonardo da Vinci,

Mechanism for Gold Processing, before 1495 |

Vincent Van Gogh’s View of Arles Across the Rhome features a typical Van Gogh scene through an atypical lens, his thick gobs of paint traded in for pen and brown ink hatching. A town can be seen across the water, a bridge connecting it to what’s across the way, and a shadowed figure in a boat is rowing in the water before us. While traveling in Arles, France, Van Gogh had to save money on materials and so turned to drawing, and this work shows his drawing style’s turn towards more rapid, fluid strokes.

Read the rest of my review here on Woman Around Town >>

|

| Vincent van Gogh, View of Arles on the Rhone River, c. 1888 |

|

| Francis Picabia, Mask and transparence, 1925 |

[/zl_mate_code]

[/zl_mate_code]